The newts and frogs wander the roads near Rodeo Beach. The ducks walk around Stowe Lake in Golden Gate Park, even more slowly than the people.

This was a solidly middle class family until Wall Street's speculative "bets" crashed their livelihood."Well, he rebuilt the engine on his car …

"And in a couple of months we'll have to choose -- will we make the house payment? or pay our local taxes -- they call them "fees"? or will we buy health insurance?" We'll only be able to do one of these ...

I don't pretend to know whether what I've just quoted is defensible as history. It might be; it might not. But I do know I am offered something worth chewing on.In most of the ancient world, the prevailing belief was that neither gods nor men could change the basic functioning of the universe, that there was a certain primordial reality that everyone needed to adapt himself to. In the Bible we have the opposite. God creates the universe, and he does not stop there. His continued interventions include also catastrophic acts of destruction -- the tower of Babel, Sodom and Gomorrah, Egypt under Pharaoh. God continues to impose his will, and indeed much of the biblical narrative is dedicated to his interventions. Every word he utters, every punishment he metes out, every act of redemption is another act of creation, for he is acting in freedom, imposing his will, changing things. One need think only of the flood, when God, having seen the depth of human corruption, “repented” at having created the world and sought to begin again. He is an inventor, forever tinkering with his imperfect work. God “re-creates the universe each and every day,” says the Talmud.

When we change things, we re-create the universe just as God does. A changed world is a new one, even when the change is small. One of our most important discoveries in early childhood is that the world is not a given, but that we can affect it: A baby pushes buttons on a toy, causing a light to flash and music to play; a toddler builds a tower of blocks; an older child invites her friends over and avoids an afternoon alone; a teenager changes his attitude toward schoolwork and begins getting better grades. All these minor successes give us a rush of the effectiveness of our will -- something especially cherished by children who are so used to having the world and its rules presented to them as unchangeable.

We often forget how easily we may be agents of change. We no longer live in a world where the crucial choices of spouses, careers, and religious commitments are dictated by our parents and communities. Our lives are our own to a degree unimaginable just a few centuries ago, and even as we grow older, we are free to make both major and minor changes in the contours of our lives. Some of these, such as embarking on a new career, marriage and divorce, or religious conversion, entail not only promise but also enormous risk and pain. But as major acts of change, they reaffirm the infinite possibilities of which every one of us is capable. In a sense, every time we exercise our will in recrafting our lives, we imitate God in re-creating the universe.

Our modern, democratic world could never have sprung from a civilization that did not believe in change the way the Bible, and pretty much no one else in the ancient world, did. Modernity, if nothing else, is the unleashing of the individual’s creative will, through political institutions that protect our right to make choices, and through the cultural reverence for the individual as a source of change. …

Of Rich's poems, I always come back to this:Art, Ms. Rich added, “means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage.”

Your Native Land, Your Life.I

When my dreams showed signs

of becoming

politically correct

no unruly images

escaping beyond border

when walking in the street I found my

themes cut out for me

knew what I would not report

for fear of enemies' usage

then I began to wonder

II

Everything we write

will be used against us

or against those we love.

These are the terms,

take them or leave them.

Poetry never stood a chance

of standing outside history.

One line typed twenty years ago

can be blazed on a wall in spraypaint

glorify art as detachment

or torture of those we

did not love but also

did not want to kill

We move but our words stand

become responsible

and this is verbal privilege

What she and her sisters-in-arms were fighting to achieve, she said, was simply this: “the creation of a society without domination.”

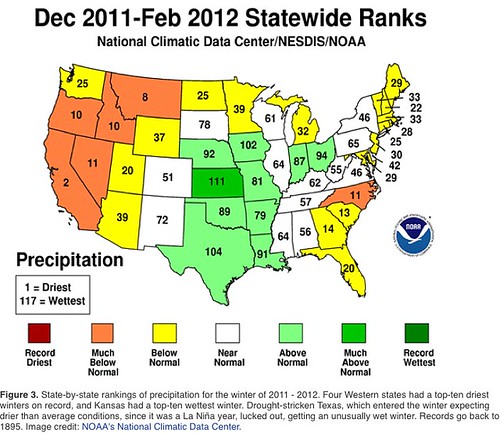

Climate Central discusses the earlier arrival of spring, regional differences, and how warming trends might project into the future.It's pretty well-documented that climate changes are affecting pollen production, pollen exposure, and allergies.

USDA scientist Lewis Ziska, among other researchers, has found that ragweed is one of the plants whose growth is most enhanced by exposure to higher concentrations of carbon dioxide. Not only does the ragweed grow faster when exposed to more CO2, it also produces more pollen. This is especially an issue in cities, which have higher concentrations of CO2 than rural areas, thanks to having a higher concentration of cars and other CO2 emitting sources. Extra bonus: There's also some evidence that allergy seasons are getting longer, as Spring starts earlier and Winter takes longer to truly set in.

Emphasis added for readability. There, that wasn't so bad, was it?First, Congress made health insurance available to millions more low-income individuals by expanding eligibility for Medicaid. Beginning in 2014, Medicaid eligibility will extend to anyone under age 65 with income up to 133% of the federal poverty level. Currently, Medicaid beneficiaries are primarily children in low-income families, their parents, low-income pregnant women, and low-income elderly or disabled individuals. The newly eligible persons will consist primarily of low-income non-elderly adults without dependent children.

Second, Congress enacted taxing measures that encourage expansion of employer-sponsored insurance. The Act establishes new tax incentives for eligible small businesses to purchase health insurance for their employees. In addition, the Act’s employer responsibility provision imposes a tax liability under specified circumstances on large employers that do not offer adequate coverage to full-time employees.

Third, Congress provided for creation of health insurance exchanges to enable individuals and small businesses to leverage their collective buying power and maintain health insurance at rates competitive with those charged for typical large employer plans.

Fourth, Congress enacted market reforms that will make affordable insurance available to millions who cannot now obtain it. Certain reforms have already taken effect, including provisions that bar insurers from canceling insurance absent fraud or intentional misrepresentation and from placing lifetime caps on benefits, 42 In addition, the Act establishes medical loss ratios for insurers, i.e., minimum percentages of premium revenues that insurers must spend on clinical services and activities that improve health care quality, as opposed to administrative costs or profits. The Act also requires insurers providing family coverage to continue covering adult children until age 26, which has led to an additional 2.5 million young adults gaining coverage. Beginning in 2014, the Act will bar insurers from denying coverage to any person because of medical condition or history, (guaranteed-issue provision), and from charging higher premiums because of a person’s medical condition or history, (community-rating provision).

Fifth, Congress enacted new tax credits, cost-sharing reduction payments, and tax penalties as incentives for individuals to maintain a minimum level of health insurance. The Act establishes federal premium tax credits to assist eligible individuals with household income up to 400% of the federal poverty level purchase insurance through the new exchanges. These premium tax credits, which are advanceable and fully refundable such that individuals with little or no income tax liability can still benefit, are designed to make health insurance affordable by reducing a taxpayer’s net cost of insurance. The credits will be available even to families with incomes at (and above) the median level, which, in 2010, was $75,148 for a family of four and $42,863 for an individual. For eligible individuals with income up to 250% of the federal poverty level, the Act also authorizes federal payments to insurers to help cover those individuals’ cost-sharing expenses (such as co-payments or deductibles) for insurance obtained through an exchange. CBO projected that 83% of people who buy non-group insurance policies through exchanges will receive premium tax credits, (20 million of 24 million), and that those credits, on average, will cover nearly two-thirds of the premium,

In addition to those incentives through tax and other subsidies to purchase health insurance, Congress assigned adverse tax consequences to the alternative of attempted self-insuring. Congress provided that, beginning in 2014, non-exempted federal income taxpayers who fail to maintain a minimum level of health insurance coverage for themselves or their dependents will owe a tax penalty for each month in the tax year during which minimum coverage is not maintained.

Whatever we may think of the verdict, we can't say the jurors didn't work at constructing a thoughtful understanding of the events.The bias intimidation charges were the most difficult to agree upon, jurors said. And what tipped the scales there, they said, was that Mr. Ravi had discussed spying on Mr. Clementi not just once, but repeatedly, even inviting his online friends to watch Mr. Clementi and the other man in a second encounter.

That, said Ms. Audet, is what elevated the case from one of teenagers behaving cruelly and insensitively to a crime.

“To attempt a second time, is what changed my mind,” she said. “A reasonable person would have closed it and ended it there, not tweeted about it.”

The webcam did not work for the second encounter; Mr. Ravi, 20, claimed that he had turned it off. But Ms. Audet said evidence suggested that he was lying. “He was at ultimate Frisbee practice,” she said, and evidence showed he then went to a dining hall. “We came to the conclusion that it was Tyler who turned off the computer to make sure he wasn’t filmed a second time.”

She added, “That hit home big.”

… Mr. Ravi’s lawyer pointed to apologetic texts that Mr. Ravi sent Mr. Clementi, in which he said he had no problem with homosexuality and even had a close friend who was gay. (At almost the exact moment he sent the apology, Mr. Clementi, 18, committed suicide after posting on Facebook, “jumping off the gw bridge sorry”).

Mr. Leverett, a student and Twitter user himself, was unmoved. “I can’t speak for everyone on the jury, but me, personally, I believe it was something where he realized what he did was wrong, and it was just too late to amend for what he did.”

Of the apology, Ms. Audet said: “My first impression was to believe what he said. Then, as we started reading stuff, we found things in there that I interpreted more as covering.

“The friend he claimed was a good friend in high school, that person was never presented as a defense witness. If that person had come forward and said, ‘Hey, we’ve been good friends, and he knows I’m gay and he doesn’t have a problem with it,’ that might have swayed me in the other direction.”

That is, the jurors were required by the way the case was framed to try to read the mind of someone who is dead. Now their conclusions may have been obvious -- and may have been correct -- but that seems a lot to ask and not, perhaps, a basis on which to deprive someone of freedom.... the jury believed that Ravi did not invade Clementi’s privacy for the purpose of intimidating Clementi over his sexual orientation. But they thought that Ravi should have known that Clementi would feel intimidated, and that Clementi believed he was intimidated, and so Ravi is guilty and going to jail.

I have to say I agree with that. The jurors concluded that Clementi was intimidated and/or humiliated because he was gay and therefore the invasion of privacy deserved the hate crime enhancement, even though what the evidence seems to show (via media accounts) is simply that Ravi was a garden variety jerk, not a dangerous intentional homophobe.Lawrence Lustberg said that subsection bases guilt "on the state of mind of the victim as opposed to the state of mind of the defendant."

In most criminal statutes, the intent of the perpetrator is a key element in there being a crime. Predicting a hard-fought appeal, Lustberg said the argument would be that "it is unprecedented for a conviction to be based on the state of mind of the victim."

"It is very worrisome to me that a defendant could be subjected to these very severe penalties based upon the state of mind of someone other than himself," Lustberg said before the verdict.

That seems right to me.Deepa Iyer, the director of South Asian Americans Leading Together, supported federal hate crimes legislation as well as related state and local laws, but says the consequences have to be proportionate to the act. Iyer notes that the automatic deportation of people with convictions amounts to double punishment.

“When these incidents occur, it’s not just the individual that’s being assaulted, bullied or murdered, it’s the entire community that’s being victimized,” said Iyer. “At the same time, when it comes around to the court system, especially around sentencing, these cases and alleged perpetrators need to be assessed for whether the punishment fits the crime.” Deportation after a jail sentence -- essentially exile for someone like Ravi, who was born in India but raised in the U.S. -- constitutes double punishment in Iyer’s mind.

That is, he thinks most of his colleagues are in thrall to various identity concerns or to an intellectual framework that has outlived whatever usefulness it once had. And so their efforts neglect what he considers the fundamental object of history: "to understand the past."If you asked my colleagues: what is the purpose of history, or what is the nature of history, or what is history about, you would get a pretty blank stare. The difference between good historians and bad historians is that the good ones can manage without an answer to such questions, and the bad ones cannot. But even if they had answers, they'd still be bad historians -- they would simply have a framework within which they could operate. Instead of which they have little templates -- race, class, ethnicity, gender and so on -- or else a residually neo-Marxist account of exploitation. But I see no common methodological framework for the profession.

Snyder, also a distinguished historian, amplifies Judt's critique. If history is as malleable a commodity as much current teaching asserts, students become unable to judge what is is real and what matters.…Before anyone -- whether child or graduate student -- can engage the past, they have to know what happened, in what order and with what outcome. Instead, we have raised two generations of citizens completely bereft of common references. As a result, they can contribute little to the governance of their society. The task of the historian, if you wish to think of it this way, is to supply the dimension of knowledge and narrative without which we cannot be a civic whole. If we have a civic responsibility as historians, this is it.

Both Judt and Snyder adhere to a standard for judging whether something is "good history" that must be infuriating to their detractors; as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart memorably declared about pornography, they claim to "know it when [they] see it." Says Judt:I think that a lot of apparently critical history is actually authoritarian. That is, if you're going to master a population, you have to master its past. But if the population has already been educated -- or induced -- to believe that the past is nothing but a political plaything, then the question of whether the play-master is their professor or their president becomes secondary. If everyone's a critic, everyone seems free; but in fact everyone is in thrall to whoever best manipulates, with no possibility of resort to fact or truth as self-defense. If everyone's a critic, everyone's a slave.

History's fundamental ethical responsibility is reminding people that things actually happened, deeds and suffering were real, people lived thusly and their lives ended in such and not other ways. And whether those people were in Alabama in the 1950s or Poland in the 1940s, the underlying moral reality of those experiences is of the same quality as our experiences, or is at least intelligible to us, and therefore real in some irreducible way.

I loved this stout declaration; it is exactly how I judge the many works I read, though I certainly can't claim these two gentlemen's erudition. I have some academic historical training and am widely read, but ultimately, I judge written history in this partially subjective manner. Simply put, I judge most of the books I read and write about within three categories:… there has to be a plausibility in your story. A history book -- assuming its facts are correct -- stands or falls by the conviction with which it tells its story. If it rings true, to an intelligent, informed reader, then it is a good history book. If it rings false, then it's not good history, even if it's well written by a great historian on the basis of sound scholarship. … My younger colleagues find this a completely mystifying proposition: for them, it's good history if they agree with it.

Some delegates walked out. This is still a brave stance for the leader of the U.N. bureaucracy. Thanks to All Out for sharing it.It is our duty under the United Nations Charter to protect the rights of everyone, everywhere. …To those who are gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, let me say: you are not alone. … I stand with you … I call upon all countries to stand with you too. … We must tackle the violence, decriminalize consensual same sex relationships, end discrimination and educate the public ...

Now we know. The Supremes spelled it out.“Criminal justice today is for the most part a system of pleas, not a system of trials,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote for the majority. “The right to adequate assistance of counsel cannot be defined or enforced without taking account of the central role plea bargaining takes in securing convictions and determining sentences," …

Justice Kennedy, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, acknowledged that allowing the possibility of do-overs in cases involving foregone pleas followed by convictions presented all sorts of knotty problems. But he said the realities of American criminal justice required to the court to take action.

Some 97 percent of convictions in federal courts were the result of guilty pleas. In 2006, the last year for which data was available, the corresponding percentage in state courts was 94.

“In today’s criminal justice system,” Justice Kennedy wrote, “the negotiation of a plea bargain, rather than the unfolding of a trial, is almost always the critical point for a defendant.”

Quoting from law review articles, Justice Kennedy wrote that plea bargaining “is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system; it is the criminal justice system.” He added that “longer sentences exist on the books largely for bargaining purposes.”

All defendants need competent lawyers throughout their encounter with the state AND we should take the death penalty out of the equation. Replacing the death penalty with a sentence of life without possibility of parole would make for more certain, less costly, and more just outcomes in the criminal justice system.The threat of execution can be enough to scare people into taking responsibility for crimes they did not commit, especially since many of these confessions come at the end of grueling interrogations in which police are permitted to lie to suspects about the evidence, or lack thereof, gathered against them. DNA evidence has exonerated a number of prisoners who are serving life sentences on the basis of these coerced pleas. As recently as 2009, the Governor of Nebraska had to release 6 prisoners, five of whom had falsely confessed, for a rape and murder that occurred more than twenty years earlier. Peoples’ lives are ruined in this process, even if they are released. Richard Danziger, a Texas man put in jail because of an associates’ death penalty-inspired plea, suffered severe brain damage as a result of beatings he received in prison for a rape he had nothing to do with.

Al-Akhbar English paints a more vivid picture of what the Syrian unrest means to the marooned Iraqis.Beyond the general protection concerns resulting from the current unrest in Syria, its social and economic impact on people of concern is likely to require UNHCR to provide them with significant direct assistance in the near future. Moreover, the current situation in the Syrian Arab Republic is likely to cause serious delays in the resettlement programme, jeopardizing refugees' access to this durable solution.

With refugees exhausting their personal resources and international assistance for public health and education programmes on the decline, new vulnerabilities could arise even among those who used to be able to provide for themselves.

It is not (so far) that either the Syrian authorities or insurgents are actively targeting Iraqis, but Syria's economic paralysis threatens their continued ability to make a living. As immigrants without legal status, they have never been able to work officially, but got by on the proceeds of informal commerce.In 2008, Iraqi activist and journalist Hana Ibrahim fled from her home in Baghdad to Damascus, taking her two children with her. They had grown up under sanctions and war, and had as such never enjoyed the level of security they found in Syria. But even that has become a thing of the past.

“For years my daughter couldn’t go out alone, because the streets had become too dangerous for girls especially. In Damascus, she felt free to do as she pleased,” said Ibrahim. “In Iraq, we had grown used to electricity cuts. Once in Syria, my children were surprised we had power round the clock. In general, life was much better for us here.”

But one year on from the start of the uprising, life in Syria has changed dramatically for Syrians and non-Syrians living there. Many face a worsening security situation, disruptions to social services, increased impoverishment, and uncertainty in the face of the future.

Al Azzawi is particularly concerned about the young people.Today, a deteriorating Syrian economy and security situation have meant that “many of the Iraqis’ small businesses have either already closed down, or are about to be forced shut. Though many of the refugees have a high level of education, they have no other means of survival,” said [Souad] al-Azzawi, [an Iraqi environmental engineer, human rights activist, and herself a refugee.] “How will they pay their rent? How will they pay their bills? How can they survive this disaster? I don’t know.”

Iraqis who have officially declared their refugee status to the UNHCR have hoped to resettle somewhere with more opportunity than Iraq in its trashed condition or an uncertain Syria. Since 2007, 28,000 of them have moved on to other countries, mostly to the U.S. and Canada. But that's just a trickle from among the millions of lives torn apart by the war President George W. launched so blithely nine years ago.“These children have the additional burden of suffering for the second time in recent memory,” she said, pointing out the psychological toll of displacement, which is often especially traumatic for the young. “They left as a result of the American invasion of Iraq, and have already had to deal with rebuilding their lives once. While in Iraq, some of them had lost friends, others had lost family members. Now, they have to face uncertainty once again. …”

Working to curb gang violence alongside Boston police, he discovered that if you could understand that gang members are rational within the terms of their setting, you could come up with rational measures that quickly cut the number of homicides, even while all the attendant horrors of poverty and inner city powerlessness still ruled in Black and brown communities. But he also learned that most intervention didn't continue to work because the three intersecting "communities" living within the agony -- law enforcement (culturally if not literally white), "ghetto" dwellers, and the street thugs -- had contradictory and destructive ideas about the others' realities. You could make short term gains, but the structures of power, poverty and policing made for back sliding into violence and misery.Everybody knows crime is down these days, it's a national success story. America's homicide rate hit almost 10 per 100,000 in the peak years; it's now about half that. But not for black men. Black men are dying, overwhelmingly by gunshot, at a horrendous pace. In 2005, black men aged eighteen to twenty-four were murdered at a rate of 102 per 100,000 (white men of the same age: 12.2 per 100,000). Recent data show that, even as homicide overall continues to decline, black men are dying more. …

That last insight is what this book is best at -- Kennedy describes for law enforcement and society at large how police methods and policing look to people on the wrong end of it. Here's lots more -- pay attention.The real problem, though, is not in our currently ineffective strategies, and the answer to the problem is not just to substitute new strategies for the old ones. The real -- the deep -- problem is what happens between communities, and how that generates the appalling situation on the ground: the communities that look at each other and say, This is your fault; the communities that see each other as toxic and malevolent; the communities that cannot imagine working together for a common purpose; the communities that do not understand how profoundly they want the same things; the communities that do not see how they are backing each other, and themselves, into corners none chose, none wants. To see what's really going on, we have to see this. …

…law enforcement has in general written these communities off. There is a powerful conventional wisdom in the law enforcement circles I live in: that these communities are at heart uncaring, complicit, corrupt, destroyed. Nobody cares about the crime, the law enforcement narrative goes, or they'd raise their kids right, get them to finish school, have them work entry-level jobs -- like I did, like my kids do -- instead of working the corners. They don't care about the violence; nobody will even tell us who the shooters are. … As long as this is how law enforcement sees the neighborhoods, they will continue to occupy them, stop everybody, arrest everybody, send all the men to prison.

The second important community is the community in even the poorest, hardest-hit black neighborhoods. It's vital, caring, resourceful; it wants what any community wants: to be safe, to prosper, for its sons and daughters to prosper. It's not happening. It's not safe, and they're not prospering. The community looks around itself, at the poverty, the violence, the drugs, and asks, why? And it has an answer. Many in the black community believe that this is all happening because we -- the outsiders, the cops, the white folks, the powerful -- want it to happen. All of it: the drugs, the killing, the destruction, all of it. …

When this is what law enforcement looks like in poor communities, you can't end violence. Nothing works.… In the hottest neighborhoods this is the dominant public narrative: The government brings the drugs in so they can put our kids in jail so the cops will have work and the private prisons can make their dividends.

Let's start with the fact that the idea, common currency in these neighborhoods, that the government is running a carefully organized racial conspiracy against black America is not as crazy as it sounds. Up until the late 1960s, when the civil-rights movement finally won out, America was a carefully organized racial conspiracy against black America. Written into the Constitution: blacks are three fifths of a person, free states will regard fugitive slaves as property. …

In these neighborhoods, the historical experience of abuse under color of law continues. It is a kind of arithmetic truth that the worst of this is in the most desperate neighborhoods, that the worst law enforcement, and the worst of law enforcement's unintended consequences, gets focused on the already most damaged, most alienated, most suspicious communities. Where the police break the law all the time. All the time.

What happens on the other side of the door when the drug guys go in: Everybody there is shouted down, manhandled, put on the floor, handcuffed. Every door opened, every room entered. Shoot the dogs, sometimes. Cereal, flour, milk poured into the sink, onto the kitchen floor. The baby's toys and videos broken open. Drawers pulled out, dumped, everything pawed through, on the floor. Beds upended, mattresses slit, furniture upended, cushions slit. The guys in armor are relieved that they haven't been shot, haven't had to shoot anybody; they're laughing, stomping around, tearing the place apart. Neighbors gather outside, watch through the door and windows, hear things. Most places when it's over the team piles out and leaves, doesn't even secure the shattered door. Anybody not arrested gets cut loose, shocky, crying. It's horrible. If it weren't the cops who'd done it to you, you'd. . . call the cops.

And we need to understand the way all this looks to the community. At best, law enforcement is not solving their problems. They are not safe, they are not secure, drug dealers own the streets, their kids are getting shot, they're getting shot. … Given the truth of our American history, it is all too easy for angry black communities to believe that this is not just incapacity: that it is malign. … Add the suspicion, or perhaps the conviction, not in fact all that wild-eyed, given history, that outsiders might be seeking to control and to oppress. It becomes not so hard to understand why conspiracy might seem a live option. Overseer, slave catcher, Ku Klux Klan, cop, DEA -- all seamless.

Residents want to know why their kids, good kids, get stopped all the time. Ministers want to know why they got pulled over and treated rudely, got treated like a drug dealer. People want to know why they're getting treated like this, the white folks in the suburbs aren't, and they're the ones driving in to buy dope. They want to know why the county is building a new jail when the ceilings in the school are falling in. They say the cops are selling dope to the corner boys. They want to know why their cousin got tuned up by the cops who arrested him. They want to know why nobody's talking about how the government is bringing the drugs in. They want to know why the cops aren't doing their job.

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, explicitly responded on NPR to Kennedy. For all his good will, she says he is still not getting it.The relentless law enforcement we see is intended to save lives, to protect neighborhoods, to bring order to the streets. I have spent my adult life with the men and women who do the work, and I know this to be true. I have no time for the easy armchair cant that says this is all about profiling and racism and bias in the criminal justice system. It simply is not so. Nobody who has ever actually been on these streets could believe it for a moment. There is disparate treatment in law enforcement, no question, but that's not what's driving the problem.

I live in one of those neighborhoods that struggles with all this. A predominantly Brown neighborhood, not a Black one -- and that makes a difference. The Mission is not a really bad place, but still a neighborhood where street murders happen with some frequency; where parents fear shootings when their children play outside; where police hang posters hoping to get leads on crimes. A gang injunction forbidding certain individuals to congregate covers the neighborhood.… you know, much of David Kennedy's work I agree with, but I think it's very easy to kind of brush off, as he does, the notion that the system operates much like a caste system if you are, in fact, not trapped within it.

... I have spent years representing victims of racial profiling and police brutality, and investigating patterns of drug law enforcement in poor communities of color; and attempting to assist people who have been released from prison, quote-unquote "re-enter" into a society that never seemed to have much use to them in the first place.

And in the course of that work, I had my own awakening about our criminal justice system and this system of mass incarceration. Probably 10 years ago, I might have shared David Kennedy's view, but I don't any longer. My years of experience and the research that I have done has led me to the regrettable conclusion that our system of mass incarceration functions more like a caste system than a system of crime prevention or control.

Now, that's not to say that many of the people who work within it, including my own husband who's a federal prosecutor, aren't well-intentioned. Many of them are. But the problem is that the structure of the system guarantees that millions of people will be swept into the system for relatively minor crimes, the very sorts of crimes that are ignored on the other side of town, swept into the system, branded criminals and felons and then stripped of the very rights supposedly won in the civil rights movement.

An Afghan soldier shot to death a 22-year-old Marine at an outpost in southwestern Afghanistan last month in a previously undisclosed case of apparent Afghan treachery that marked at least the seventh killing of an American military member by his supposed ally in the past six weeks, Marine officials said.

The American staff sergeant suspected of killing 16 Afghan villagers had been drinking alcohol — a violation of military rules in combat zones — and suffering from the stress related to his fourth combat tour and tensions with his wife about the deployments on the night of the massacre, a senior American official said Thursday.

KABUL, Afghanistan — A Turkish helicopter crashed into a house in Kabul on Friday, killing at least 12 NATO service members and two civilians, the American-led coalition and Afghan police said.

Enough.Women visiting relatives at a notorious men’s prison on the edge of Kabul have in recent weeks been subjected to invasive body-cavity searches at the order of the prison’s commandant, who has told guards and American officials that the measure is needed to keep out contraband, Western and Afghan officials said.

…Having been repeatedly rebuffed, the Americans on Thursday tried to use the best lever they have: they cut off all American financing to Pul-e-Charki until they can confirm that the invasive searches have stopped, two Western officials said. The United States has spent about $14.2 million on improvements at the prison since June 2009.

Why aren't protesters screaming from the rooftops about this administration's adoption of pre-emptive permanent detention, about a verbal renunciation of torture that leads to no prosecutions of proud war criminals like Dick Cheney, and an assertion of a right to kill individuals anywhere in the world without any adversarial process? Certainly, these retreats from the rule of law and historically evolved norms of human social decency are as grievous as those of the previous regime. Where's the outrage?"Trial by jury, trial by fire, rock, paper scissors, who cares? Due process just means that there is a process that you do," Colbert said. "The current process is apparently, first the president meets with his advisers and decides who he can kill. Then he kills them."

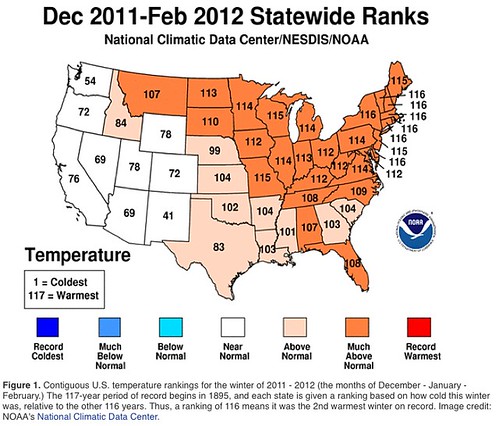

If you lived in the Northern Plains, Midwest, Southeast and Northeast, it seemed like winter never really arrived this year--27 states in this region had top-ten warmest winters. … If you live in the Midwest, you saved a bundle this winter on heating and snow removal costs. In Minneapolis, where the low temperature falls below 0°F an average of 30 days each year, the temperature fell below zero on just two days. ...In a normal winter, there are 13 days with sub-zero temperatures in Chicago. The coldest it got in Chicago this winter was a relatively balmy 5°F on January 19.

"The dangers of carbon dioxide? Tell that to a plant, how dangerous carbon dioxide is …"

I wonder whether he gets the same junk mail I'm getting as I come within 3 months of Medicare: official looking envelopes that say in tiny obscure print "non-governmental document." I bet he does; the vipers that scam older people make their money on volume. Though most of us throw their crap out, a few elders get taken in and that's makes the "offers" profitable.Mitt Romney turns 65 Monday, making him eligible for Medicare. But his campaign has confirmed that he will not use the government health care program. "No, he's keeping his current private insurance plan," a Romney source told CNN.

It's hard to know what to say about the latest from the U.S. war on the Taliban in Afghanistan … or should it be called the U.S. war on Afghans? Here's the Times:An AP photographer saw 15 bodies between the two villages caught up in the shooting. Some of the bodies had been burned, while others were covered with blankets. A young boy partially wrapped in a blanket was in the back of a minibus, dried blood crusted on his face and pooled in his ear.

Someone named Shaun Narine from Fredericton, Canada managed to say something semi-sensible in comments on the atrocity story:PANJWAI, Afghanistan — Stalking from home to home, a United States Army sergeant methodically killed at least 16 civilians, 9 of them children, in a rural stretch of southern Afghanistan early on Sunday, igniting fears of a new wave of anti-American hostility, Afghan and American officials said.

Residents of three villages in the Panjwai district of Kandahar Province described a terrifying string of attacks in which the soldier, who had walked more than a mile from his base, tried door after door, eventually breaking in to kill within three separate houses. At the first, the man gathered 11 bodies, including those of 4 girls younger than 6, and set fire to them, villagers said.

… Adding to the sense of concern, the killings came two days after an episode in Kapisa Province, in eastern Afghanistan, in which NATO helicopters apparently hunting Taliban insurgents instead fired on civilians, killing four and wounding another three, Afghan officials said. About 1,200 demonstrators marched in protest in Kapisa on Saturday.

My Canadian military friend got out with the rest of their forces a year ago. When are U.S. forces going to cut their losses and get out?I think that people in Afghanistan can probably accept the idea that a soldier will, from time to time, go crazy. It's not that surprising, if very unfortunate. I think that what may be worse is the incident mentioned in passing in this article -i.e., the death of four Afghan civilians and wounding of three more after being mistakenly fired upon by US helicopters. These "mistaken deaths" happen far too often and are the result of a matter of policy. This is the kind of thing that has made Afghans disgusted by and resistant to the ongoing American/NATO occupation.