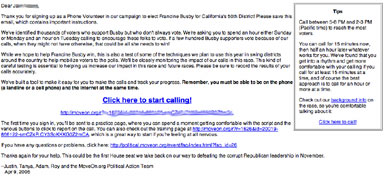

This is a good book. For those of us who hang around liberal political blogs like MyDD and DailyKos, a lot of what Jerome Armstrong and Markos Moulitsas Zuniga have to say may seem old news. Yeah, we know that Republicans are smart, determined, fully funded, unscrupulous, corrupt liars who manipulate fundamentalist suckers to gain power, that the bought-off and bought-up mainstream media let them get away with it, that the Democratic Party is in thrall to loser political consultants and Beltway bubble-dwellers. ...Yadayadayada. ... Nothing new to see here. But, of course, there are lots of folks for whom this diagnosis of our political woes, cogently explained, is news. So hooray for Jerome and Markos.

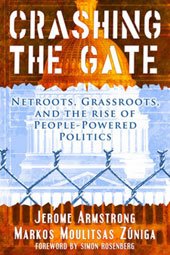

This is a good book. For those of us who hang around liberal political blogs like MyDD and DailyKos, a lot of what Jerome Armstrong and Markos Moulitsas Zuniga have to say may seem old news. Yeah, we know that Republicans are smart, determined, fully funded, unscrupulous, corrupt liars who manipulate fundamentalist suckers to gain power, that the bought-off and bought-up mainstream media let them get away with it, that the Democratic Party is in thrall to loser political consultants and Beltway bubble-dwellers. ...Yadayadayada. ... Nothing new to see here. But, of course, there are lots of folks for whom this diagnosis of our political woes, cogently explained, is news. So hooray for Jerome and Markos.What Crashing the Gate did for me was not so much teach me anything new as remind me of things I've learned in long years of activism. A few follow.

Ordinary politics, power politics, and ideological politics

Ordinary Politics is an unpleasant necessity that many citizens will only stick a toe into in the hope that this will enable them to go back to the real business of living -- family, love and leisure -- enjoying a modicum of peace and security. Ordinary Politics people think those of us who live and breathe activism are nuts, irritating nuts. They are at least 85 percent of everyone in a stable society. It takes something close to disaster to get them engaged; George W. Bush's regime might just do that.

Then there are power politics people. Power politics people love the mechanics of getting and holding power. These days, Karl Rove is the prototypical power politics guy, but a decade ago the guy was Dick Morris or James Carville. Lots of us on the blogs are power politics people. We want to rebuild a Democratic Party and we get our rocks off sticking it to the other side. We enjoy jostling for position in party committees and campaign organizations. Jerome and Markos seem to me to be representative of a new generation of power politics people whose mission at this time is to replace previous generations of Democratic movers and shakers. Goodness knows, it's time for Bob Shrum et al. to go -- give'em a good kick guys. Power politics folks are probably 5-7 percent of everyone, rare birds indeed.

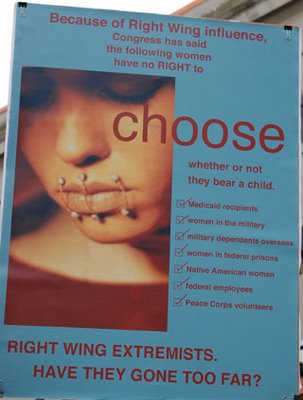

Just as rare, also maybe 5-7 percent of everybody, are ideological politics people. These folks want power, but unlike the power politics people, they focus on what that power is for, often to the detriment of being smart about how to get it. Ideological politics people give the Dems their values. They are the conscience of the party, demanding that it stand for economic, racial and gender equity, that its policies contribute to building international law and planetary sustainability.

To the power politics people, the ideological politics people are often a damn nuisance. Jerome and Markos take this line, labeling them obstructive "special interests." This is over doing it, repeating a staple of right wing spin (something these authors are quick to criticize when others do it.) Women and working people are not "special interests"; along with (and as members of) the racial minority communities, they are the Democratic Party. Some of the policy positions that the institutions of the women's movement and the labor movement elaborated back when Democrats were the party of government may need some reframing to suit current (abysmal) social conditions. But without the progressive ideological orientation brought by the ideological types, there is no good reason for most people to put any energy into the hard struggle to win power from the Republicans. The ideological politics people don't give a damn about the Democratic Party as such, they just want their policy aims enacted. If Democrats aren't there for them, they go home or wander off and become Greens.

(For a cautionary tale of what happens when the power politics people completely remake a formerly progressive party solely to create a vehicle to win and hold power, have a look at Tony Blair and New Labour over in Britain. Sure they keep winning Parliamentary majorities, but to what end? To do away with democracy, civil liberties and the social safety net? To act the part of Bush' poodle? Try reading "Hollowing out of the Labour Party" to get a taste of this.)

Obviously, my sympathies are with the ideological politics folks, though since I actually work in campaigns, I can think of many moments when I wanted wring the necks of my more purist comrades. No, I don't think taking out the recycling is as important as getting the phone bank started. Real world politics is a messy business.

A Democrat by default only

Above all, Crashing the Gate reminded me that I am only a Democrat by necessity. One of the surreal by-products of out current proto-fascist situation is that all oppositionists have had to hang together, the potential cost of wandering apart looking too great to risk. In 2004 we even had antiwar activists working to elect Kerry, while Kerry was prescribing "more troops to Iraq." In the midst of such insanity, it is all too easy to start thinking that the Democratic Party is a real entity to which one has a real allegiance. But that's simply not the case for most of the political actors I just described. The power politics people will usually hold the reins of a big tent outfit like the Dems. But what they value is the reins, not the party itself. The rest of us have other interests.

That's not a bad thing, just a reality. In our current political straits we have no choice but to try to rebuild the Democratic Party as vehicle for change. It is an odd vocation for about 87 percent of us, but there it is. Thanks to CTG for some useful ideas on how to get it done.