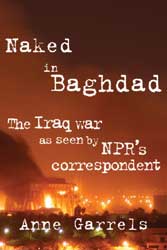

The injured friend to whom I am currently lending a hand indulged an impulse toward reclaiming political equilibrium that I didn't allow myself: she acquired many of the first wave of the U.S. books about our explosion of imperial hubris under Bush. There's Richard Clarke on how we could fight terrorism better his way and Aaron Glantz from occupied Iraq. But the prize I've long wanted to read is Naked in Baghdad: The Iraq War and Aftermath by NPR correspondent Anne Garrels. So yesterday I did.

The injured friend to whom I am currently lending a hand indulged an impulse toward reclaiming political equilibrium that I didn't allow myself: she acquired many of the first wave of the U.S. books about our explosion of imperial hubris under Bush. There's Richard Clarke on how we could fight terrorism better his way and Aaron Glantz from occupied Iraq. But the prize I've long wanted to read is Naked in Baghdad: The Iraq War and Aftermath by NPR correspondent Anne Garrels. So yesterday I did.This is not a deep and meaningful account of the U.S.'s epic belly flop. This is one smart, resourceful older woman sharing what it was like to report from Saddam Hussein's corrupt dictatorship in its last days and then live through U.S. bombing and an apparently random shelling of the journalist's hotel once the Marines finally arrived.

I remember liking listening to Garrels reporting in the run up to the invasion: she never sounded convinced by the Bush boys bluster. And she wasn't, though having lived through the last days of the Soviet Union in Moscow, she had a clear slant on the vicious, collapsing dictatorship all around her. She states her own views gently:

Garrels did listen and record. In light of subsequent events, what Iraqis told her seems frighteningly prophetic:March 21, 2003... I am of many minds about the need and justification for this war. I have seen how brutal Saddam's regime is, but I am not convinced that he continues to have weapons of mass destruction. The United States has not made a persuasive case, and American diplomatic efforts appear lame. I also worry about the U.S. government's staying power to do what needs to be done when it is all over. Americans have shown they have a very short attention span. My ambivalence, however, makes it easier for me to cover the situation, to just listen to what the people here say.

- "While this family and their friends blame Saddam Hussein for many of their problems and believe Iraq does need a change, they resent what they see as American arrogance. What gives Americans the right to change things that are not theirs to change? they ask. This is a constant refrain. They express pride in Iraq and its history."

- "Zanab is a Shiite Muslim, one of the majority who has endured relentless repression at the hands of Saddam's Sunni-dominated government, but she says the divide, so apparent until the war, has disappeared under a new unity forged against the Americans. She calls them aggressors who have only come for oil."

- "Even if they are initially defeated, there are Iraqis who take comfort in their history, insisting they are the toughest Arab people to subdue. Ultimately, they say, no foreigner has been able to control this territory successfully. "

- "Pulling down statues makes for good television, but as I saw in Moscow in 1991, it doesn't ultimately signify much. ... Wiping out the past doesn't mean coming to terms with it. ...[A] group of men sits outside their shuttered shops....They are...in shock at the sudden collapse of the regime. 'I've never known freedom,' thirty-three year old Ali al-Abadi says....'We want a just government, but we want a just Iraqi government.' ... The Iraqi opposition in exile which has been courted by the United States inspires no confidence. ...They want nothing to do with anyone who has just come back from living in luxury abroad while they themselves have suffered at home."

I also love how she put an older woman's peculiar combination of sexuality-free invisibility combined with accumulated experience to work for her reporting. On the one hand, she passed, marginally, as "one of the boys" when dealing with officialdom and technology. Yet on the other hand, she was able to hear the stories of Iraqi women who might have been hidden from men. This reporter knew who she was, so she could see what she saw with much less self-concern than might have gripped a young up-and-comer struggling to establish her journalistic chops.

Garrels also profited from her neither fish nor fowl status as a non-commercial radio reporter. Her husband, Vint, in one of the "Brenda [Starr] Bulletins" he emailed to their worried friends, gave a clear description of her wonderfully anomalous status as the old woman of a contingent of no more than 16 Americans who stuck out the invasion in Baghdad.

Above all, I loved the interplay in this between book between Garrels' narrative and Vint's bulletins. (I do have more experience than most Americans with having a loved one make themselves a voluntary witness to a war.) At one point Vint took Garrels off the email list because he didn't want to overburden her in the heat of battle; later he sent her large batch of these letters all at once. Anne Garrels knew what she was getting:The journalist community of the Palestine Hotel is very much a guy's world divided between print journalists and TV types. Somewhere suspended in her own space is our Annie -- neither print nor television; too old to be a babe, too serious to be dismissed -- but not really one of the gang, either. And her brutal schedule of constant updates doesn't allow her to socialize that much. It doesn't bother her; she works better this way. Moreover, it amuses her to see how the little fissures in the journalistic hierarchy get established.

This "war reporting" is as well a lovely picture of a mature relationship. The disastrous details of the U.S. invasion have sunk into history, but Garrels' book remains very worth a read.I am overwhelmed, and not a little daunted by his extraordinary prose....A friend has called them 'love letters,' and indeed that is what they are.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete