This morning's screaming front page headline in the San Francisco Chronicle read:

California's Growing Diversity Doesn't Extend to the Ballot Box.

I'm tempted to respond, yeah -- what else is new? After all, I put out the following in 1995 (using the previous year's figures) while developing a plan for a campaign against an initiative to outlaw affirmation action:

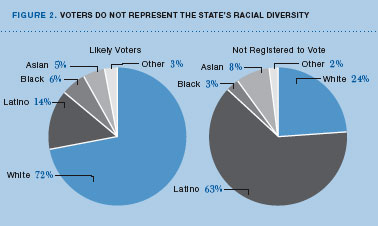

From that perspective, the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) study just released documents progress. By its reckoning, the segment of the electorate that is not white has jumped from 19 percent to 28 percent in the intervening years, while concurrently the state changed from roughly 52 percent white to more like 46 percent. Still, the PPIC paper once again amply demonstrates that the California electorate is out of phase with the population.The California electorate (that fraction of the population which is eligible to be registered, is registered, and votes) is very different from the demographic picture presented by the state’s residents as a whole. For example, 14 percent of voters were between 18 and 29 years old, while actually 28% of Californians are in that age range. Only 14% of the electorate had household incomes of less than $20,000, compared to 26% of state households. Fully 50% of the voters were college graduates, as opposed to 20% of Californians over 18. Most strikingly, and saliently for the purposes of discussing the anti-affirmative action vote, though nearly half the state’s residents are members of the various communities of color, the electorate in 1994 was 81% white.

Where the PPIC study shines is in the attitudinal data integrated with the simple demographic facts. I tend to be skeptical of the notion that non-voters' attitudes are significantly different from voters' opinions, except possibly on such divisive hot button topics as the series of "white fright" wedge measures (anti-immigrant, anti-affirmative action, anti-bilingual education) the state endured in the 1990s. But this study homes in on economic attitudes, demonstrating clearly that non-voters would be willing to reopen the debate that pits taxation against public services and lean toward the latter. They would even overturn the destructive sacred cow of California politics, Prop. 13. This 1978 initiative freezes property taxes for long time homeowners, making the resources available to local governments dependent on the state government's also precarious fiscal health.

Before reading this study, I was unaware that most new voters register "decline to state" rather than choosing a political party.

This is not the case in the street level voter registration drives I see; most canvassers come home with a substantial majority of Democrats. Evidently other forms of registration including motor voter and mail-in don't have the same results.Political party membership has also declined over the past 16 years. The percentage of California adults registered as major party voters has dropped from 54 percent to 43 percent.... For the first time in modern California history, the majority of adults do not belong to one of the major parties.

This survey doesn't explore why new voters are choosing "decline to state." I can speculate based on a combination of anecdote and experience:

- Some new citizens don't want to risk public affiliation with a "side." They want to keep their heads down.

- Because of extreme gerrymandering, almost no state legislative seats or Congressional seats are competitive. Local elections in many jurisdictions are non-partisan. Voters consequently have little sense that party identification means much, except perhaps in Presidential primaries.

- Candidates, whether responding to voter preference or out of timidity, seldom emphasize their party. If the standard bearers don't think party is important, why should the voters?

- Local party structures are close to non-existent in most areas so they aren't out there bringing in party-identified voters. A great deal of the registration funding and work that does exist passes through non-profit organizations that are precluded by law from encouraging party affiliation.

That is, all players in the current system have at least some incentive to keep the unrepresentative, but well understood, electorate that we have. The people likely to need and want structural change aren't voting. Changing that is a long project, the work of a political generation, not a four year election cycle.Growth and change in the electorate could initially result in more political instability, as elected officials, candidates, parties, and initiative campaigns reach out to a larger, more diverse, less partisan, and unpredictable electorate.

No comments:

Post a Comment