This week, South Africa did what seems to be beyond most of the United States: it legalized gay marriage. The vote in Parliament, where the elected African National Congress (ANC) commands a huge majority, followed a ruling by the country's Constitutional Court that unequal marriage rights amounted to illegal discrimination against gays and lesbians under the 1997 Constitution.

In the spring of 1990, my partner and I were witnesses to some of the history that led to this groundbreaking decision. We had the privilege of working in Cape Town providing tech support to a newspaper that was part of the "Mass Democratic Movement" against apartheid. Nelson Mandela had been released from prison in February; the ANC, which had led the struggle against racial oppression, had just been legalized; and the whole society was bubbling with an awareness of new possibilities.

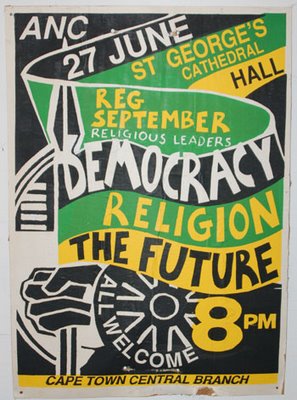

The poster pictured above is a visual artifact of that heady moment: in a style reminiscent of 1960s Haight-Ashbury rock concerts, in the ANC's black, green and gold colors, it promoted what in other times would perhaps seem a pretty dry panel discussion. In Cape Town that year, big questions about ultimate meaning, about democracy, about freedom, were all up for grabs. I snared the poster off a lamppost; they blanketed the town.

Into this vibrant atmosphere, ANC leaders who had spent many years in exile returned to their country. In particular, Albie Sachs, arrived. Sachs is an attorney who defended ANC members under the apartheid government, was jailed without trial by that government, escaped into exile, and then was almost assassinated by a bomb placed in his car in Mozambique by South African security agents, losing an arm and the sight of an eye. On his return, his job was to listen to the hopes of the various "struggle" organizations within the country in preparation for drafting a post-apartheid constitution.

Into this vibrant atmosphere, ANC leaders who had spent many years in exile returned to their country. In particular, Albie Sachs, arrived. Sachs is an attorney who defended ANC members under the apartheid government, was jailed without trial by that government, escaped into exile, and then was almost assassinated by a bomb placed in his car in Mozambique by South African security agents, losing an arm and the sight of an eye. On his return, his job was to listen to the hopes of the various "struggle" organizations within the country in preparation for drafting a post-apartheid constitution.One of the groups Sachs met with in Cape Town was the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Activists (OLGA). Cape Town then and now was "the San Francisco" of South Africa, the place where behavioral limits are broader than in most of the country. Still this seemed an astonishing breakthrough for gays and lesbians in a country where homosexuality was at best something to snicker at. The meeting was possible because OLGA campaigned not only for gay rights, but also was a recognized "nonracial," anti-apartheid group. Nonetheless, the quite open-minded journalists at the paper where we worked were surprised by this open overture from the revered ANC to the gay community.

The paper got an invitation to a press conference held by Sachs and OLGA; our co-workers insisted we come along. We jumped at the chance -- and were bewildered by the dirty looks we got from some of the OLGA people. Much later we understood. Every gay and lesbian in Cape Town had wanted to attend the event. OLGA members had to limit attendance; they thought we were some local lesbians sneaking in, until informed that we were "press."

The statement Sachs made at that press conference remains an extraordinary document in the history of gay liberation. Some excerpts from a transcript we made:

When the new Constitution came into effect in 1997, equal rights for gays and lesbians were included. And last year the Constitutional Court overthrew South Africa's statute defining marriage as solely a union between one man and one woman, holding the provision a violation of the Constitution's general mandate for equal protection for all and its specific mandate against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The author of that opinion was Justice Albie Sachs. The legalization voted on last week is the follow-on to that decision."The question of homosexuality has never been treated in an open and honest way in South Africa. The first thing that has to be done is get the question out in the open and for persons who stand to be most affected by any future dispensation to say themselves what they would like to see. This is part of a very extensive process of consultation and debate, based on the principle that people must write their own constitution. ...

"We don't see the constitution as being the product of a few enlightened (or unenlightened) lawyers. People must make their own input. Somebody said that a constitution is the autobiography of a nation. Everybody is part of the nation. Everybody has a right to contribute.

"In the case of homosexuality in South Africa, there is a special pertinence in this phase where we are overcoming apartheid. The essence of apartheid was that it tried to tell people who they were, how they should behave, what their rights were. The essence of democracy is that people should be free to be who they are. Any full democracy in South Africa, in my view, should be such as to encourage everybody to be who they are. ...

We already know the people in OLGA -- they've been very active in general in the anti-apartheid struggle, they have standing and prestige in the movement, and there is a strong feeling they shouldn't be in any way discriminated against because of their sexual preference. But this goes a little beyond that -- it is part of people in general defining what their own rights should be. ...

"There is too much fear in South Africa in general. We want people to be free, to feel free. This is one more area, in my own view, where there appears to be oppression. We are against oppression and we want everybody to feel they are part of the nation, they are part of the new South Africa, as part of a general program against discrimination, against marginalizing people, against this idea of telling people who they are and what they are. ..."

1 comment:

It's good to see you posting about this - makes me proud to be South African!

Post a Comment