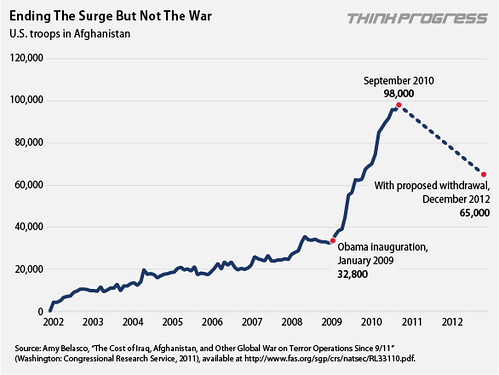

The Eisenhower Research Project based at Brown University has created a new website devoted to exploring what the misguided United States wars since 9/11 have cost this country -- and the unfortunate countries and people in the way of the injured, but infantile, imperial colossus. Many of their findings reproduce what people seeking peace have attempted to highlight for a decade, but it seems worthwhile to reproduce the suggestive conclusions from the executive summary.

- While we know how many US soldiers have died in the wars (just over 6000), what is startling is what we don’t know about the levels of injury and illness in those who have returned from the wars. New disability claims continue to pour into the VA, with 550,000 just through last fall. Many deaths and injuries among US contractors have not been identified.

- At least 137,000 civilians have died and more will die in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan as a result of the fighting at the hands of all parties to the conflict.

- Putting together the conservative numbers of war dead, in uniform and out, brings the total to 225,000.

- Millions of people have been displaced indefinitely and are living in grossly inadequate conditions. The current number of war refugees and displaced persons -- 7,800,000 -- is equivalent to all of the people of Connecticut and Kentucky fleeing their homes.

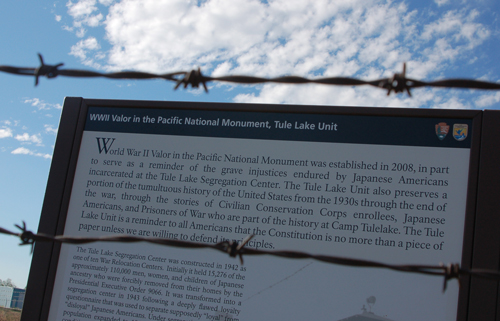

- The wars have been accompanied by erosions in civil liberties at home and human rights violations abroad.

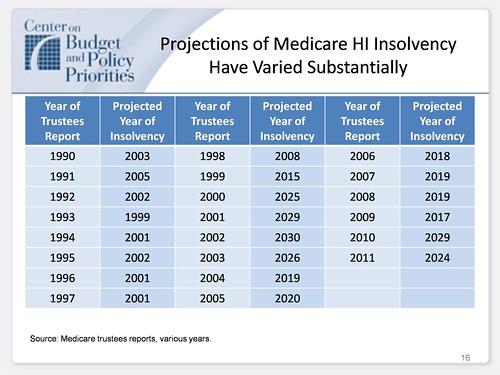

- The human and economic costs of these wars will continue for decades, some costs not peaking until mid-century. Many of the wars’ costs are invisible to Americans, buried in a variety of budgets, and so have not been counted or assessed. For example, while most people think the Pentagon war appropriations are equivalent to the wars’ budgetary costs, the true numbers are twice that, and the full economic cost of the wars much larger yet. Conservatively estimated, the war bills already paid and obligated to be paid are $3.2 trillion in constant dollars. A more reasonable estimate puts the number at nearly $4 trillion.

- As with former US wars, the costs of paying for veterans’ care into the future will be a sizable portion of the full costs of the war.

- The ripple effects on the U.S. economy have also been significant, including job loss and interest rate increases, and those effects have been under-appreciated.

- While it was promised that the US invasions would bring democracy to both countries, Afghanistan and Iraq, both continue to rank low in global rankings of political freedom, with warlords continuing to hold power in Afghanistan with US support, and Iraqi communities more segregated today than before by gender and ethnicity as a result of the war.

- The armed conflict in Pakistan, which the U.S. helps the Pakistani military fight by funding, equipping and training them, has taken as many lives as the conflict in neighboring Afghanistan.

Another bullet point seems both encouraging and problematic:

- Serious and compelling alternatives to war were scarcely considered in the aftermath of 9/11 or in the discussion about war against Iraq. Some of those alternatives are still available to the U.S.

In fact, the freedom of movement of both the administration (which seems to have some glimpses of this) and the entire political system are profoundly constrained by the destruction wrought by the wars of the '00s. Too many good options available in 2001 -- for example effective, cooperative international police work against terrorists -- are gone, undermined by the jack-booted rendition and torture policies adopted by the Bush administration. Terrorism suspects captured in Europe can fight extradition to the United States because we are considered a torture-practicing country with an impoverished grasp of basic human rights.

The costs of these wars are even greater than the Eisenhower Research Project study -- we have only begun to appreciate them.

H/t Washington Note for pointing to this study.