This is not a joke. "Artisans, silversmiths, basket makers and traditional hairdressers are situated in an unique African steppe landscape" says the brochure. Norbert Finzsch, Professor of History and Provost of the University of Cologne wrote:

It is obvious that the conveners do not understand the historical implications of their project. . . . The way Africans and African Americans in Germany are perceived and discussed, the way they are present on billboards and in TV ads prove that the colonialist and racist gaze is still very much alive in Germany.

This is the direct result of forty years of German colonialism and twelve years of National Socialism. People of color are still seen as exotic objects (of desire), as basically dehumanized entities within the realm of animals. This also explains why a zoo has been selected as site for the exhibit. It is necessary to remind the organizers that in the history of "ethnographic shows" African and German African individuals were used as objects for anthropometric tests and ethnological investigations of highly questionable scientific benefit. Many of the artists who performed in these shows in the 1920s and 1930s died from malnutrition and as a consequence of bad living conditions. The Nazis employed a policy of eugenic control, resulting in forced operations to limit the biological reproduction of African Germans or in downright incarceration in concentration camps. Survivors of this policy had to gain a living as performers in exotic shows.

The Augsburg exhibit thus fails to acknowledge the political and social history of persecution in Nazi Germany.

German speakers can read more here.

You can send a letter of protest to Frau Dr. Barbara Jantschke (Director of the Zoo at Augsburg).

But while we're railing at the arrogant racism in displaying human beings in a zoo, we need to be aware of some US history. In 2000 Martha R. Clevenger of the Missouri Historical Society described this show at the St. Louis Worlds Fair in 1904 still making excuses for the display, while cautioning that we contemporaries also carry the prejudices of our own time:

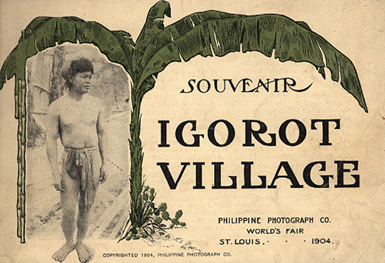

In 1904, a group of Igorot men and women, members of a Filipino tribe, were exhibited on the grounds of the St. Louis World's Fair. . . [they served as] a human exhibit to justify the new American program of overseas Imperialism. . . .

The architects of the Igorot display had good intentions. They were interested in the new science of anthropology, which they understood to be "man's study of man," and hoped that an examination of the people of the Philippines might teach something of value. They were promoting a political and social agenda, which included not only furthering of American Imperial interests, but also disseminating the American values of education, economic prosperity, democracy, and progress. In practice, however, these lofty goals were corrupted by a competing agendas: by the need to attract visitorship to the World's Fair, by the human tendency to gape at that which is different, and by the inequities inherent in ensconcing human beings in a human zoo. . . .

For example, in order to attract press coverage and hence visitors, Fair planners required the Igorots to perform the dog feast on a daily basis. In reality (if understand correctly) the dog feast was a rare and infrequently preformed ceremonial event at home in the Philippines.

At the Fair, the dog feast, and the efforts of Fair planners to procure dogs for the Igorots, became great fodder for the popular press. Today, this is what we remember about the Igorot.

By-putting people on exhibit, Fair planners effectively turned them into objects, to be inspected, to be studied, to be stared at and peered at, and inevitably to be denigrated, pitied and despised. In an age before the Internet, a group of people such as the Igorots, who looked different, who dressed in traditional fashion, and who were required to kill, cook and eat dogs on a daily basis were an exotic curiosity. Under these circumstances, it was very difficult for Fair planners to keep the Philippine Exhibit from effectively degenerating into a sideshow.

The Germans running the Augsburg zoo don't get it; the organizers of the St. Louis Fair didn't get it; and when we distance ourselves from those 1904 anthropological imperialists, we don't get it: other people do not exist for us, for our exploitation or our entertainment. We're all in this human condition together, none stranger, more exotic or less valuable than any other. Get over it.