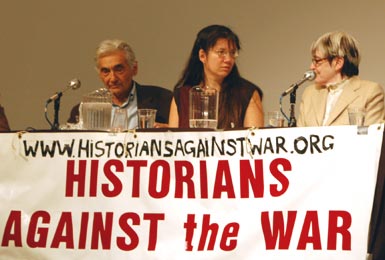

Howard Zinn, Andrea Smith, and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz at the conference plenary

Many years ago I was on track to become a professional historian, but I jumped off that train. I like to joke that I decided that it was more interesting to try to make history than to write it -- and this past weekend's Historians Against the War conference confirmed my understanding that I am better cut out for activism than for academia.

Aside from keynoter Rashid Khalidi, almost all the speakers made a point of insisting that attempts to predict the future on the basis of the past are an improper role for an historian. Okay, I know that "past performance is no guarantee of future results" as all prospectuses say, but I do study history to help me discern possible futures -- my activist gut growls: if I can't do that, what is the point? Besides, though historians claim to eschew prediction, in fact many of their papers easily lend themselves to it: neither John Mason Hart who sketched the trajectory of U.S. empire nor James Carter who outlined the history of profiteering in U.S. wars would ever suggest these trends were unlikely to continue.

I left the presentations (again Khalidi aside) feeling that a lot of issues that matter to me were unexplored. What follows are my musings on general issues at the intersection of academic history and activist intellectuals.

Some questions

Do the Bush administration's militarist and authoritarian activities and/or the war in Iraq suggest that we are now experiencing something new in U.S. history? Or is the predominant theme continuity with the long story of U.S. imperialism? Most presenters did not explicitly address this question, a distinction that seems to me crucial to activists hoping to accurately understand our challenges.

Should antiwar inquiry (and potential action) be focused on the objects of U.S. attack (on the "Middle East") with the implied need to prioritize "Middle Eastern" voices and scholars who can explicate those societies? Or, should antiwar scholarship aim predominantly to understand (and change) U.S. society -- an effort that points to lifting up different speakers? The study of history has some light to shed on this perennial challenge I think, but this conference both ignored and straddled the question.

Although the title of the conference was "Empire, Resistance and the War in Iraq," very few of the speakers addressed what seems to me a pretty critical question for popular resistance: are we faced with a U.S. empire still on the rise and feeling its oats or, perhaps even more dangerously, with a wounded beast struggling to arrest its decline? Our perspectives on that question color what we see and help determine what we do. I think I would have learned quite a bit if more panelists had addressed this other than tangentially.

Some observations:

What passes for legitimate knowledge as defined by academia over the last 100 years or more has been understood as existing across an unbridgeable chasm from the teachings of religion(s). It would not be an exaggeration to say that respectable contemporary ways of knowing, as much in the humanities and the social sciences as in the hard sciences, are based on an assumption that religious understandings of the world are in the process of withering away. Consequently, the conference confirmed that historians seem pretty much flabbergasted and certainly not very competent to describe the contemporary situation in which religious passions are moving populations as much in North America as in the Islamic world. This ignorance is not a good thing from the activist perspective.

Over and over, speakers seemed to run up against a wall created by a professional doctrinal imperative that academic knowledge must be only descriptive, not prescriptive. In history, that means we'll tell you what happened, perhaps acknowledging the point of view from which we observe it, but we can't tell you how we evaluate what happened, whether we approve or condemn it. The latter sort of interaction with the data is considered unprofessional. That is all very well, but this professional stance stymies social and political action even to defend the possibility of free inquiry, much less to combat empire. Adherents to this code are left unprepared for some inevitable challenges. For example, how to answer the student who admits that pursuit of empire is murderous, but if that is what it takes for people in the U.S., for our own families, to live a good life, what is wrong with empire?

Having pointed to all these big questions, I certainly don't want to trash this conference. This activist was glad to have the opportunity to step back and think about these questions with a room full of smart, informed, committed people.

No comments:

Post a Comment