New York Times food writer extraordinaire

Mark Bittman wants us to understand that fast food is not cheaper than home-cooked food. I haven't done the pricing research, but I am willing to believe him, up to a point. Where I part company is that he doesn't seem to assign any value to costs -- beyond cash outlays -- that make home-cooked food seem more expensive. First there is the figuring out what to cook. Then there is the time and whatever energy is required to go procure what you decide to cook. Finally there is the cooking itself. That's all actually quite burdensome.

He does give an oblique nod to these factors that encourage us to substitute McNuggets for real food, but then never follows up on his own observation. Here's the bit that seems about right to me:

The core problem is that cooking is defined as work, and fast food is both a pleasure and a crutch. “People really are stressed out with all that they have to do, and they don’t want to cook,” says Julie Guthman, associate professor of community studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and author of the forthcoming “Weighing In: Obesity, Food Justice and the Limits of Capitalism.” “Their reaction is, ‘Let me enjoy what I want to eat, and stop telling me what to do.’ And it’s one of the few things that less well-off people have: they don’t have to cook.”

I wish he'd followed up on that, but he jumps right back to charging fast food companies with working (as I am ready to believe they have) at getting us addicted. There's much more going on here.

***

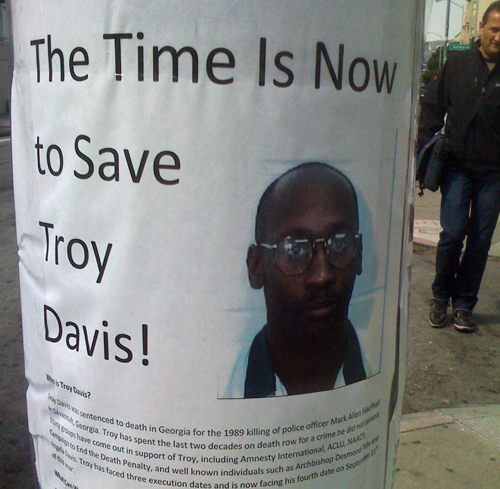

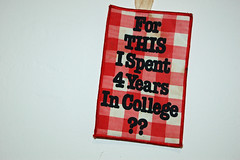

This potholder is part of my inheritance from my mother. She graduated from college in 1930, she was proud of her intellectual accomplishments, and she thought the expectation that as a proper wife she would be put food on the table for her husband every night was an unwelcome burden. She thought cooking was drudgery. It also never occurred to her that anyone else would do it, even to the extent of going out to dine more than three times a year. So she soldiered through the task unhappily almost every day of a more than 60 year marriage.

Bittman would have approved of her understanding of what constituted edible food; she didn't believe you could buy vegetables and fruits out of season; she even made her own jam and pickled peaches. But she hated all kitchen tasks and the food she cooked showed it. She was probably one of the most atrocious cooks who ever lived; some of the stuff she thrust at us nightly was pretty awful. She had no conception of cooking as an art form -- and it wasn't anything she aspired to improve in.

We're only a generation away from women whose relationship to food was this kind of visceral resentment, a stand-in for their general sense that women's allotted roles constrained their potential. That's certainly part of what enabled the fast food marketers to gain their ascendancy.

***Resentful women who thought of food prep as part of their oppression are not the only ones who've looked to reduce the amount of time people spend cooking. Part of the vision of nineteenth century socialism was that food prep would be moved outside the home, in a word, "socialized." No longer would individuals (women) be mired in putting food on the table. Soviet Russian industrial enterprises actualized this in what are described as dreary, low-quality cafeterias. Real human beings most likely weren't so grateful to have every last speck of their private lives taken over by what amounted to their employers.

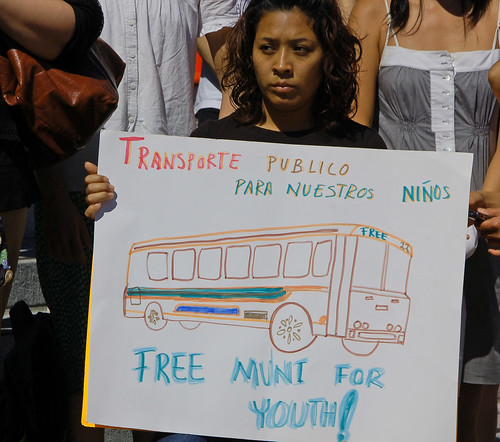

Yet the most imaginative among contemporary U.S. capitalist enterprises also go in for moving the feeding of their workforces to the worksite. Google is famous for its free gourmet restaurants for employees. During a recent civic argument about giving tax abatements to encourage Twitter to locate in a blighted area of central San Francisco, opponents pointed out that Twitter's workers weren't likely to be a boon for neighboring businesses since they could eat for free inside the company compound.

Clearly some people besides McDonalds think they get some benefit from moving eating away from the home.

***For the last few summers, we've had the decidedly unusual privilege of spending some time in a household where Bittman's prescriptions are possible and followed. Abundant, if pricey, local produce, fresh-caught fish and farm-raised lamb are readily available. Our host cares about food and is a creative gourmet cook. There are hardly any nearby fast food places -- and those that exist are local, not the ubiquitous chains.

And nonetheless, the "daily dinner discussion," the preclude to shopping, still feels burdensome. Even where good food is the rule, thinking about it comes to feel arduous.

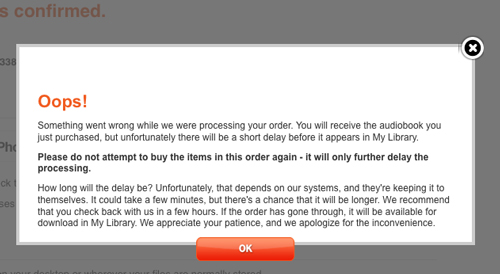

***This rant isn't going anywhere very meaningful. Ironically, we are currently enduring a home kitchen upgrade that has us camping in a couple of rooms in the front of the house, cut off from our bedroom and living in chaos.

The truth is, we don't cook much. We come home from work tired and frequently default to the cheap urban take-out readily available within blocks of here: tacos, burritos, chili, chicken caesar salads, pupusas, falafel, less often Chinese or pizza. These come from small enterprises that cook their foods in-house -- we are fortunate not to live in middle-America.

What we do in a kitchen is often just "assembling." Several times a week we create a big salad out of vegetables from the excellent fruit stand around the corner. I don't think Bittman would consider our diet that bad. I consider it a vast improvement on the the diet of my youth or what I see many of my neighbors eat. But we don't really cook much.

Perhaps the new kitchen will inspire us with more enthusiasm. It certainly will be somewhat more functional and cleaner than its antiquated predecessor. But there will still be the thinking ahead and procuring hurdles to jump. Will we be willing to do that?