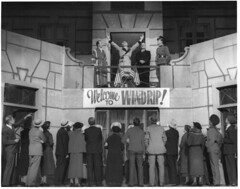

On October 27, 1936, It Can't Happen Here, by Sinclair Lewis, opened simultaneously in twenty-one theaters in seventeen states. The Los Angeles Yiddish production, pictured here, featured Morris Weisman as "Buzz" Windrip. Federal Theatre Project Collection

For those of us who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, at least in the north and west, US fascists seemed pretty darn remote, even quaint. Of course there were segregationists clubbing freedom riders and blowing up kids in churches, but that seemed another country and certainly against the law of the land. There was a nutcase named George Lincoln Rockwell who paraded around with swastika armbands. But threatening fascists were figures of European history, monsters our parents' generation had defeated in World War II.

Sinclair Lewis's novel springs from a premise that certainly would have seemed far-fetched in those days: a demagogic fascist senator, one Buzz Windrip, wins the nomination of the Democratic Party for the presidency in 1936, after Franklin Delano Roosevelt fails to find solutions to the economic and social distress caused by the Great Depression. (This certainly seems wildly farfetched today as we know Roosevelt swept 46 states in that year; however, before opinion polls, progressives really feared that attacks by right wing demagogues might sweep him from office. One of the best accounts of this period I know of is the second volume of Blanche Wiesen Cook's biography of Eleanor Roosevelt, The Defining Years, 1933-1938.)

Roosevelt, in horror, bolts the Democrats to form the Jeffersonian Party, splitting the opposition to Windrip with the Republicans. The US majority rallies to the man who promises everything to everyone (except for Jews and Negroes) and fascism is voted into office.

Lewis's description of the emotionally charged political environment rings too many bells for my comfort:

The conspicuous fault of the Jeffersonian Party, like the personal fault of [its candidate], was that it represented integrity and reason, in a year when the electorate hungered for frisky emotions, for the peppery sensations associated, usually, not with monetary systems and taxation rates, but with baptism by immersion in the creek, young love under the elms, straight whisky, angelic orchestras soaring down from the full moon, fear of death when an automobile teeters above a canyon, thirst in a desert and quenching it with spring water -- all the primitive sensations they found in the screaming of Buzz Windrip.

The rest of the novel catalogues the horrors perpetrated by the fascist regime so blithely elected.

Lewis ends his novel, still bemoaning the ignorance of the people in general. After terrible atrocities, some revolted, but the revolt stalled:

. . .because in the America, which had so warmly praised itself for its "widespread popular free education," there had been so very little education, widespread, popular, free, or anything else, that most people did not know what they wanted -- indeed knew about so few things to want at all.

There had been plenty of schoolrooms; there had been lacking only literate teachers and eager pupils and school boards who regarded teaching as a profession worthy of as much honor and pay as insurance-selling or embalming or waiting on table. Most Americans had learned in school that God had supplanted the Jews as chosen people by the Americans, and this time done the job much better, so that we were the richest, kindest, and cleverest nation living; that depressions were but passing headaches and that labor unions must not concern themselves with anything except higher wages and shorter hours and, above all, must not set up an ugly class struggle by combining politically; that, though foreigners tried to make a bogus mystery of them, politics were really so simple that any village attorney or any clerk in the office of a metropolitan sheriff was quite adequately trained for them. . . .

I have to admit that this description depresses me: arrogant nationalism, anti-intellectualism, and failure to grasp and act on our own economic interests seem still among our country's besetting sins. I know most teachers try hard to impart something more, but through emphasis on testing rote learning and "starving the beast," we more and more make our schools places of confinement for the young, rather than arenas in which they learn to exercise independent thought.

*A Midsummer Night's Dream

No comments:

Post a Comment