Barbara J. Scot's Nepal doesn't exist anymore, if we are to believe the US State Department's travel advisories or National Geographic's Adventure magazine. A fumbling, autocratic hereditary monarchy has collided hard with a Maoist insurgency based among long-suffering peasants. Over 11,000 Nepalese are dead; progressive modernizers of all stripes have been violently pushed to the sidelines.

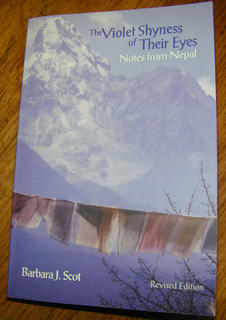

Barbara J. Scot's Nepal doesn't exist anymore, if we are to believe the US State Department's travel advisories or National Geographic's Adventure magazine. A fumbling, autocratic hereditary monarchy has collided hard with a Maoist insurgency based among long-suffering peasants. Over 11,000 Nepalese are dead; progressive modernizers of all stripes have been violently pushed to the sidelines.In The Violet Shyness of Their Eyes: Notes from Nepal, Scot reports her 1990 experience teaching English to young students in the growing tourist town of Pohkara. Scot has a realistic and refreshing sense of her own insignificance in bringing Nepal into modernity: she describes herself and other Western development workers as animated by "some vague feeling of wanting to share in the abundance our society has amassed." In the end, she knows the Nepalese will have to find their own way; this makes it easier for her to realize that the demands of her own relationships at home mean she should leave before her year commitment is completed.

While looking for her own path, Scot observed Nepal with a sharp and compassionate eye; for me, the value of this book is in occasional perceptive gems along the way. I'll share a couple:

In 1990, these students did not yet know the pervasive individualism and competitiveness of a modern capitalist society. Do they now? And are their lives less poor and filthy in consequence? I am sure the answer is not simple."I have been giving tests to see how well individual students have mastered the material. That is almost an impossibility. It's such a circus to get each one to do her or his own work instead of sharing it with the whole row. I have to laugh. Americans here have a lot of self-righteous cant about cheating. I don't think cheating is quite the right word. In Nepal it's considered selfish not to share. Those who know are obligated to help the ones who don't know. . . .On the whole, I rather like the cooperation. A lot of teaching goes on that way too, with academic students helping the ones who have more difficulty. . . ."

Or this:

On the one hand, how easy a life this seems, knowing your duty and doing it. On the other hand, how sad, never to imagine new possibilities, never to strike out beyond conventional expectations. In particular, how limited a life this must be for those who start off one down, whether peasants, or women, or gay people."I rise to wash before it is light. I walk a quarter mile to the village well. Other women are already there with water jugs. They are used to me now and even take my bucket and fill it out of turn. I say thank you in English since there is not really a word for it in Nepali -- only danybaad, which is used by foreigners. There is not even a concept for it in Nepali, for you do not expect to be given thanks for doing what is required of you by your dharma, religious duties. What you are required to do in this life is all predetermined by what you did in your past life. Your responsibility is simply to perform the tasks well for that will determine in what position you will be reborn. "

Globalization means above all that such static societies don't have a chance. For some their demise means vast suffering, for others vast opportunity. The only certainty is now rapid change. It is not at all clear the human species can sustain itself through this challenge, but we have no alternative.

No comments:

Post a Comment