Before I visited Nepal and trekked in the Everest region, I knew little about the later life of Sir Edmund Hillary, the New Zealander, who, with the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, first summited the world's highest mountain in 1953. Hillary died in 2008 at 88. I was glad to find in Kathmandu a dog-eared copy of Hillary's late-in-life autobiography View from the Summit and read it on the way home.

I'm just old enough to have a vague memory of the news of the two men's triumph on the mountain, all mixed up with the coronation of Elizabeth II, the first TV broadcast I remember. It took this book to make me aware of the complicated nationalist, post-colonial political ramifications that engulfed the returning climbers. It had been desperately important to Tenzing that a Sherpa should be one of the first people to reach the summit; on their return, he was pressed by Nepalese to sign a statement that the accomplishment was primarily his doing, while Hillary tried hard to credit both men. Hillary describes himself as an innocent, hyper-fit, somewhat sheltered, bee-keeper in those days, oblivious to the excitement their reaching Everest's peak would create.

Nationalist aspirations then ran into unpleasant realities of several sorts. Though Tenzing was fiercely proud of his Sherpa heritage, he actually lived in and was a citizen of India, and did not much identify as Nepalese. Meanwhile, the Brits, still harking back to empire, thoughtlessly gave more of their kudos to Hillary. Thanks to Tenzing's wife's insistence (Sherpa women don't keep mum), his family accompanied Tenzing to England for the excitement, but Hillary got the starring role. In later years, Hillary claims to have been aware something was wrong (racist) about this.Strangely enough, hearing it stated over the BBC made me realise positively almost for the first time what an achievement it had been. I had innocently thought that it would be of interest to mountaineers, but not particularly to anyone else -- but I was being proved very wrong. ...

As Hillary explains in the autobiography, for the rest of his life, he was always viewed in the role of the conqueror of Everest. At first, he used his celebrity to win leadership of a New Zealand expedition to the Antarctic. Later he and his family spent summers camping in U.S. national parks as gear-testers and celebrity endorsers for Sears Roebuck. He organized a jet boat expedition that travelled the length of the River Ganges in India and eventually served as New Zealand's ambassador to that country.... A small stool was placed in front of the Queen, I knelt on it, a short be-jewelled sword was put in her hand, she touched me lightly on each shoulder and said, "Arise, Sir Edmund." Whether I wanted it or not, I was now a knight and expected to behave as one. It was quite a change from my early days as a bee farmer in New Zealand.

There was only one thing on this great occasion that made me feel slightly uncomfortable. It would have been nice if Tenzing had received a knighthood too. He was given the George Medal, the highest civilian award for bravery in Britain, but in view of his great contribution to the expedition it would not have been unreasonable for him to have received he same decoration as I did. After all, I could hardly be regarded as knightly material in those days either.

But none of that was what he set his heart on. Rather rapidly, whatever the extraordinary physiological anomaly was that enabled him to acclimatize relatively easily to high altitudes as a young man deserted him. Quite a lot of the book is about Hillary hiking or being carried down from high Himalayan places with severe cerebral edema. The heights had turned on him.

He was well aware who took care of him.

I sure get that! I had the same sense that the Sherpas and other mountain people we met in the Khumbu region thought we'd die if left to our own devices. When I came down with pneumonia, they did anxiously assist me. This care felt willing, not in any way either servile or like a necessity to promote tourism: they simply understood themselves to be capable of living in these places and we were not, so we must be cared for.... Mingma, and the other Sherpas he recruited to build and climb with us, tough and competent themselves in their mountain environment, never really believed we could cope on our own. They would try and ensure we 'sahibs' carried only light loads, and would worry if we were going any distance without Sherpa guidance.

So, beginning in the early 1960s, Hillary took up the work of his later life, raising funds and building hospitals and school in the remote Everest region.

The regional airport at Lukla was his project. Before it was built, people and supplies had to travel on foot for two weeks over a 15000 foot pass to reach the area.

We visited the hospital built at Kunde.I was still energetic but no longer the lead climber. I was the planner and organiser and ran the whole operation. We built a hospital at Kunde ... In response to petitions from local villages we constructed half a dozen new schools. We built a number of bridges over foaming mountain rivers and brought fresh water to villages with plastic pipes. To save carrying hundreds of loads on men's backs for the seventeen-day walk from Kathmandu, I decided to try and find another suitable site for an airfield.

... Jim [Wilson, Hillary's co-worker] had a rather amazing experience. He was approached by a group of farmers from the small village of Lukla, which was located in a small tributary valley at 9,000 feet. They had some land for sale and thought it would be suitable for an airfield. They even suggested that the wind always blew in the right direction! How hill people who knew nothing about airfields could possibly make this sort of judgement I do not know. but when we went up to Lukla we agreed that they were right. And best of all we wouldn't be destroying a lot of arable land. One third was in rough pasture, one third in heavy scrub and the last third in terraced potato fields. It certainly wasn't flat, the rise from bottom to top was over a hundred feet, but this wouldn't be a problem to a STOL (short take-off or landing) aircraft. Even the negotiations for the land were relatively easy. I purchased it on behalf of the Nepalese government. for a total of $635 -- quite a substantial sum in that area in those days. ...

Altogether I had paid out just over $2,000 for land and labour. ...Lukla quickly became the busiest mountain airfield in Nepal and the gateway to Everest.

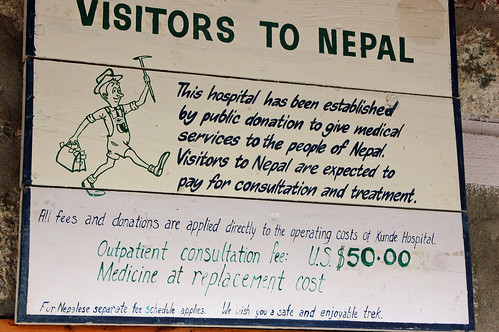

Their fee schedule made a lot of sense to me.

From the hospital, we walked on down to the regional high school at Khumjung, another project built because of Hillary's work with international climbing groups and philanthropic institutions.

Sign on the entrance arch.

The wide school yard easily accommodates several hundred studens.

Korean climbers had contributed the most recent building.

Back in Khumjung village proper, women washing clothes can thank the Hillary projects for running water.

I liked Khumjung the most of the places we visited on our trek. It seemed prosperous, enjoying some of the fruits of modernization, yet very much a town where Sherpa culture survived the relatively small trekker influx and thrived. Tourism and indigenous cultures often throw up ugly by-products, including a sense of mutual exploitation. In Khumjung, perhaps I missed things, but I didn't feel that common tension.

Sir Edmund Hillary was completely clear on what he valued most in his life.

It is interesting in these days, when I have a warm relationship with all the people of Nepal, to look back on the Everest era when I was largely resented by the Nepalese and I wasn't particularly enthusiastic about them either. ...

Achievements are important and I have revelled in a number of good adventures, but far more worthwhile are the tasks I have been able to carry out for my friends in the Himalayas. They too have been great challenges in a different way -- building mountain airfields and schools, hospitals and clinics, and renewing remote Buddhist monasteries. These are the projects that I will always remember.

1 comment:

Thank you for this information about Sir Edmund Hillary and the projects that were accomplished after 1953. I didn't know about these. I appreciate the pictures as well. Your perspective as a climber who was cared for is invaluable.

Post a Comment