General Jones speaks aloud what what once a heresy but is becoming a commonplace: the United States isn't going to be the global hegemon, the "top nation," forever.“It’s historical fact that great nations and empires all have a beginning and an end,” said James Jones, a retired U.S. general, former national security adviser to President Barack Obama and outgoing chairman of the Atlantic Council, speaking Friday in Washington at a forum hosted by his think tank. “There’s a naive belief in our country that there’s some sort of destiny, that the primacy of the United States is ensured for some reason forever. I don’t think that’s the case.”

When Barack Obama was in the White House, I always harbored a suspicion that we had a president sophisticated enough to understand that the responsibility of any person leading this country was to wean us off the drug of empire as gracefully as possible. Over time Obama seemed to accept that he wouldn't be allowed to do that job. The entire apparatus of elite power --governmental, military, media, and corporate -- sustained the inertia of empire. There were visible deflection points: Obama's failure to close Guantanamo, his panicked response to the underwear bomber (remember that one?), his reluctant campaign against Gaddafi in Libya. It remained easier, safer, to give in to the momentum keeping the US population scared stupid rather than to teach us that our world hegemonic moment (roughly 1918-2001) was slipping away. The country needed a new understanding of its role in the world, but if Obama understood that, he never dared tried to sell it. During his terms, we lost a chance to get there without feeling nearly the pain the victims of our empire have experienced at our hands. Doubt that? Read about what we're leaving in Iraq after more than a decade of unnecessary dumb war.

We now have a president who has no discernible interest in or capacity to perform any task unrelated to his own profit and glory. This week we've seen him order a pullback from Syria and Afghanistan, outcomes to be welcomed. But he certainly isn't thinking through consequences or implications.

But just because under the Trump regime, coherent US direction is AWOL, the pushing and pulling of rival powers isn't over. Apart from and alongside climate change, the underlying theme of current world events is still the question what happens after US empire wanes or is pushed aside, most likely by an insurgent China. (Russia is making information war on our society, but John McCain had that one right: with an economy smaller than Italy's, that benighted nation is merely "a gas station run by a mafia that is masquerading as a country.")

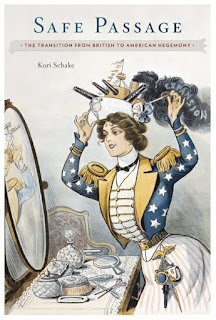

Kori Schake's Safe Passage: The Transition from British to American Hegemony is her account of what English speakers probably think of as the last time one world empire was superseded by another. It is an historical book, but not really a work of history. Rather, she cherrypicks a series of episodes to advance a theory of international relations about such transitions. I wouldn't read it looking for narrative of what happened, but I greatly appreciated the insights which her particular slant offered on incidents in the US past.

Some examples:

- That remarkable exercise in early American national hubris, the Monroe Doctrine, which warned off old Europe from the trans-Atlantic continents

showcased what America would become as a powerful state. It would assert the universality of its values and advocate the adoption of its domestic political arrangements. Monroe’s declaration, then, can be seen as a regional claim to principles that would become universal as American power itself became universal.

- She makes the case that the constraints that kept British elites from following their instinctive inclination to ally with the Confederacy during the Civil War were in part a consequence of English speaking emigration to the upstart America.

I can't help thinking that our unusual historic practice of bringing immigrants on board the good ship USA as full citizens might still be a source of strength in our dealings with their countries of origin. I suspect China considers anyone of Chinese background still Chinese (and solely Chinese) while we still have (despite Trump) considerable capacity to absorb people from other places as genuine citizens of this contradictory nation. And that goes from people arriving here from places as different as Somalia, Guatemala, or Estonia. In this we remain an oddity among a world of inward focused nations.Aligning Britain with the Confederacy risked aggravating two worrisome issues for the British government domestically: disaffection among urban workers still without political representation in Britain, and the deepening hostility of British immigrants in America. On both these counts, the United States was uniquely able to reach into Britain’s domestic debate, and during the Civil War it actively did so. ... Acting against the Union required weighing foreign policy advantage against risk of domestic damage, a calculation that America—because of its more participatory form of government—was uniquely able to impose. ... English, Welsh, and Scottish immigrants were staunch Union backers, like their German counterparts. All of these communities might become conveyor belts of insurrection back to home countries—if the United States were able to “weaponize” them.

... Debates over whether to become involved in the American Civil War show the first glint that the composition of another nation’s people had the ability to affect Britain’s governance of its own. The predominance of bloodline in determining nationality for other countries of the international order gave the United States a unique advantage, one that was coming to salience in building and sustaining American power as a dominant force in the international order. ... America’s values served to constrain the choices of its international adversaries by using the aspirations of their own citizens against them.

- Schake argues that American white settlers' long war to dispossess and often exterminate the continent's native inhabitants set the template for US militarism and empire. She is unblinking in calling out the ugliness of 19th century white America's drive for territory and dominance.

... from the French and Indian War in 1754, what would become the U.S. Army was fighting Indians, and Americans were consumed with questions of territorial security from Indian threats.

... U.S. Indian policy was directly a function of its democracy; America was not only a government that was illiberal in the nineteenth century but Americans were an illiberal people. The West became American only with the decimation of Indian ways of life. ... For Europeans, the purpose of empire was to harness indigenous inhabitants for the economic gain and political control of an external power. What is exceptional about the closing of the American West is that the policy was not merely conquest of indigenous inhabitants but their extermination or deportation to free the land up for settlement by immigrant Americans. ...

... depredations against Indians never received the attention in their time that slavery has in the American imagination. African slaves were held in physical bondage, forced to labor under close supervision, beaten and killed for underperforming, and sold as property irrespective of the bonds of matrimony and parentage; their suffering is unique in the American experience and much to be lamented. But Native Americans, too, suffered horrifically at the hands of both the American government and American citizens, and the taking of their lives, livelihood, and freedom nearly as completely did not at the time—and does not in our time—receive the attention those sins deserve. ...

... An accurate portrait of America rising needs to come to terms not only with what was gained by American settlement of the West but also with what was lost. Gained was a country of continental expanse, social and economic mobility, breathtaking tolerance for turbulence and risk, wealth creation on a scale not previously imagined, an abiding belief in the necessity and righteousness of armed force, ennoblement of the individual crafting his or her own fate in a harsh wilderness, urbanization of the industrial revolution balanced by rural landowners, and the genius of the founders’ political structures accommodating both in the respective houses of Congress.

What was lost—if indeed, it was ever truly possessed by immigrants in America—was the upholding of the political creed that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, and that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These truths were not self-evident to many Americans that flooded into the West in the second half of the nineteenth century. ...

And Schake's assessment of the new transition which we may be living provides food for thought and much to worry about:

... a dominant China is likely to recast the rules in ways that extrapolate to the international order its domestic political ideology, just as America did. Hegemony with Chinese characteristics would be a very different international order from the one America has fostered in its hegemony. It would encourage and support other authoritarian governments politically, financially, and socially. ... China lacks an ideology likely to appeal to America in the seductive way America’s ideology appealed within Britain and beyond. Without such an ideology, any hegemonic transition will require imposition by force.

No comments:

Post a Comment