Watching MAGA panic about the existence of trans and gender variant youth and by extension their elders, I realized I'd seen something very like this before. This is a country all too easily led into periodic hysteria about sex and gender, especially when it comes to actual children. Trump and the Republican Party are fanning the flames of fear for political gain.

Does this seem familiar? It certainly could. I remember when our culture in the 1980s was obsessed with the McMartin Preschool abuse trial. Something terrible must have happened ... or not. From a New York Times retrospective [gift] by Clyde Haberman:

... Starting in 1983, with accusations from a mother whose mental instability later became an issue in the case, the operators of a day care center near Los Angeles were charged with raping and sodomizing dozens of small children. The trial dragged on for years, one of the longest and costliest in American history. In the end ... lives were undone. But no one was ever convicted of a single act of wrongdoing.

Indeed, some of the early allegations were so fantastic as to make many people wonder later how anyone could have believed them in the first place. Really now, teachers chopped up animals, clubbed a horse to death with a baseball bat, sacrificed a baby in a church and made children drink the blood, dressed up as witches and flew in the air — and all this had been going on unnoticed for a good long while until a disturbed mother spoke up?

Still, McMartin unleashed nationwide hysteria about child abuse and Satanism in schools. One report after another told of horrific practices, with the Devil often literally in the details. ...

... Inevitably, perhaps, the mass frenzy over supposed Satanism and sexual predation invited comparisons to the Salem witch trials and to McCarthy-era excesses. Americans do seem prone episodically to this kind of fever. ...

Witness the widespread panic a few decades ago when people around the country convinced themselves that evil neighbors were handing children poisoned Halloween candy and apples embedded with razor blades. Arthur Miller highlighted this phenomenon in his 1953 play, “The Crucible,” which invoked the Salem trials to comment on a contemporary abuse, the scattershot McCarthy hunt for Communists ...

It seems to me obvious that Trump and MAGA are playing a very tired, very American, tune ...

So what's the other political party doing in response to MAGA's fantasies and bigotry? Far too often, cowering in closets. Most Democratic politicians are too timid to take on the assault on emerging medical science and anthropological understanding that the experience of many contemporary Americans is forcing into the light.

Parker Molloy, a Chicago media journalist, has some advice for timid Democrats:

There's a glaring omission in all the Democratic hand-wringing about trans issues: actual trans people. ...

The disability rights movement has a motto: "Nothing about us without us." It's a simple principle that Democrats have completely abandoned when it comes to trans issues. Instead of talking to us about our lives and needs, Democratic strategists talk about us as an abstract political problem to be solved. ...

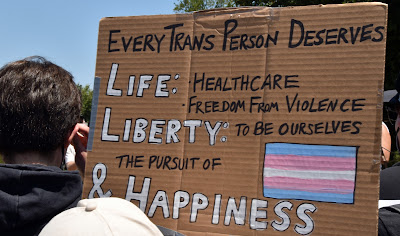

If Democrats actually bothered to have these conversations, they'd discover something ... we're not asking for much. We're not demanding special privileges or radical restructuring of society. We mostly just want to exist in public without harassment and access the same healthcare everyone else takes for granted.

By and large, trans people are not demanding (who even asked for this?) that people announce their own pronouns or whatever corporate/HR nonsense Democratic politicians think trans people want...

Talk to trans kids and their parents, and you'll hear the same themes repeatedly: They want to use the bathroom in peace. They want to play sports with their friends. They want their teachers to use their names. They want to go to school without being bullied. They want to see a doctor when they need to.

These aren't radical demands. They're the baseline expectations of any child in America.

Talk to trans adults like me, and the asks are similarly modest: Keep our jobs without discrimination. Update our driver's licenses to match our appearance. Access medical care our doctors recommend. Walk down the street without fear. Again, these aren't special rights. They're basic dignity.

But Democrats can't make these arguments because they don't know our stories. They've treated us as a constituency to be managed rather than human beings to be heard. They've let Republicans define who we are and what we want because they've never bothered to ask us ourselves.

This is more than just morally wrong; it's politically stupid. When you don't know the people you're supposedly defending, you can't defend them effectively. When you treat someone's existence as a political liability rather than a human reality, you've already lost the argument.

... they need to reframe the debate. Republicans aren't protecting children; they're weaponizing government to bully kids. They're the ones obsessed with bathrooms, genitals, and controlling people's bodies. Democrats should make them own that weirdness. ...

Democrats need to connect trans rights to broader freedoms. This isn't about special privileges or ideology. It's about the government staying out of personal medical decisions. It's about families, not politicians, making choices about their children's health. It's about the freedom to live your life without constant government surveillance of your gender.

These are winning arguments if Democrats would bother to make them.

... they need to tell human stories. Trans people aren't abstractions or political footballs. They're people's children, siblings, friends, and neighbors. When Republicans attack trans people, they're attacking real families in every community. Democrats need to make that real for voters.

.. Democrats need to show some backbone. Voters respect politicians who stand for something, even if they disagree. What they don't respect is cowardice. Running away from every fight Republicans pick doesn't make Democrats look reasonable. It makes them look weak.

Democrats have been down this road before. It leads nowhere good. You can't build a political coalition by constantly throwing people out of it. You can't inspire voters by standing for nothing. You can't protect some children by agreeing that others are disposable. ...

Get over yourselves, Dem politicians. If you can learn just enough to be real, people will respect you. Most of us aren't on the side of witch burners, soiling our pants and fleeing phantom dangers. You won't win the QAnons, but there are plenty of other people who might be willing to stop panicking, if you modeled some guts.