The largely forgotten final verse of the U.S. national anthem, before blatantly obliterating any barrier between church and state, proclaims: "thus be it ever when free men shall stand, between their loved homes and wars' desolation..." Less than 200 years ago, the prospect of death and devastation as a consequence of defending one's homeland from invasion was real and immediate to residents of the United States. My great, great, great grandmother, Margaret Kinsman Marsh St. John was one of those free women -- I find it instructive to remember her in these days when my country has come to stand for destruction of other people's countries all across the globe.

In December of 1813, the young United States was at war with its imperial nemesis, Great Britain. More immediately for settlers of western New York, skirmishes had gone on for a year along the Niagara River border with Canada. On the tenth of that month, U.S. General George McClure sought to end British incursions by teaching a lesson: his forces burned the Canadian village of Newark (now the quaint tourist town of Niagara on the Lake). Locals on the American side of the border were horrified; they accurately assessed the balance of forces and feared they would be next. According to historian R. Arthur Bowler: "McClure's action raised a storm of protest.... The burning of a defenseless town was rightly seen not merely as an act of wanton cruelty but also as an invitation to British retaliation in kind."

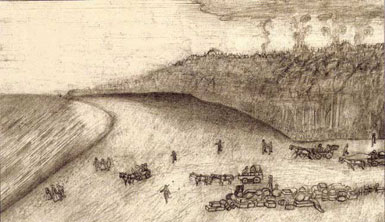

Buffalo settlers flee the British attack. A drawing by LeGrand Canon St. John, son of Margaret St. John, now in the possession of the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.

The British did retaliate rapidly. They raised an army of 1400 men, many from the native population that largely bet that the remote Brits would be less intrusive neighbors than expansive U.S. settlers. This force crossed the river at Lake Ontario. Within three weeks they had seized the fort at the mouth of the river and pushed south, burning the settlement that later became Niagara Falls, New York, and other towns along the way.

In the bustling Buffalo settlement, residents panicked. They raised 136 militia men to join a poorly trained detachment of U.S. troops, but most of the Americans ran away in front of the British advance. Meanwhile, settlers grabbed up a few belongings and fled on wagons and on foot.

My ancestor, Margaret St. John, was not able to get away. She had already had a very bad war. Her son, Cyrus, had died of camp distemper in December of 1812. Her husband, Gamaliel, and another son, Elijah, both drowned on June 6, 1813 while crossing the Niagara River to provision American troops occupying Fort Erie in Canada. In December1813, she still had responsibility for eight living children. A son in law managed to evacuate most of the family, but Margaret St. John and two daughters remained to attempt to preserve the family house and a roadhouse with hotel that provided the family's livelihood.

Family lore reports that when the British-led Indians came to loot and burn on December 30, Margaret St. John marched up to a British officer and demanded that he not allow his troops to make a widow homeless and destitute. The St. John women watched in terror when the native irregulars split the skull of Mrs. Lovejoy in the house across the street. The St. John hotel was burned, but the family home, where the women hid, was left standing, the only house that survived the British invasion.

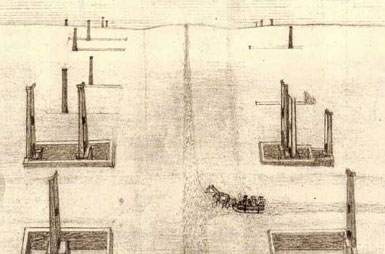

Chimneys were that was left of Buffalo after war's desolation swept through.

At least one chronicler of these events reports that the St. John family was well paid for feeding other survivors who crept back into town after the British invaders left. Those who can preserve some property sometimes do quite well on wars. The Niagara Frontier recovered rapidly from this destructive episode. Within months, settlers were again building up the city to serve as a transport point for Great Lakes shipping. The St. John children thrived and became prosperous citizens of the revived Buffalo.

I sincerely hope that our misguided "leaders" are not setting most of us up to relearn these lessons of human history -- but I don't have any confidence that this country can forever escape the ebb and flow of power grasped and overthrown. Unfortunately it will be the unconscious ordinary souls who just struggle to get by who suffer most.

1 comment:

Jan, Excellent posting. Thanks.

I've spent a lot of time thinking about why it is that Americans seem so disengaged from and disinterested in our occupation of Iraq. The reason that you've identified--that the memory of war on our native soil is distant and weak--seems right. I doubt that many Americans--including me--have any idea what it would be like to live in a war zone, and we do not have first or second-hand knowledge of living under such conditions (though I have a record of my ancestors struggles during the Civil War).

On the Fourth of July here, I was struck by the continuous, and often ear-splitting, sounds of fireworks going off all around my house in the mission. Throughout the night as these bangs echoed through my house, my first thought was that this must be what it could sound like in Iraq or any other war-torn city. I could not hear in the noise sounds of celebration or fun. Rather, I fixated on how indifferent most Americans seem to feel about the military occupation being carried out on our behalf in Iraq.

For most people, the fact that the U.S. is occupying Iraq makes no pratical difference in their day-to-day lives.

Of course, this is the way the Bush administration wants it. They know that by allowing only the poor and marginalied to fight the war--and for their families to bear the ultimate burden of the war--they can hide the true consequences of the war from most middle and upper class Americans and continue to pursue a policy of occupation.

I commend you for your effort to inform us on the realities of war and occupation, and to try to change the way Americans understand what we're doing in Iraq. Keep it up.

Post a Comment