After nearly a week, I may be ready share some semi-coherent thoughts about the exhilarating immigrant marches last Monday. I do believe we are seeing something that does not fit neatly into our existing political categories. Because it is new, and because it is not mine, I am a little hesitant to attempt analysis -- but here goes...

And there are vast numbers of these people. Estimates say 12 million U.S. residents are now undocumented. Fully thirty-three percent of U.S. population growth in 2004 came from immigration according to the National Geographic quiz some of us have been playing with. When such a large group suddenly makes itself visible, it is hard not to take notice.

Furthermore undocumented immigrants are truly poor people; when they risk even the little that they have in order to assert their dignity and humanity, their protest carries a moral weight quite different from the set piece acts of "civil disobedience" that have characterized much middle class agitation for the last 30 years. For an undocumented worker, the possible consequences of political protest are literally incalculable; fortunately there have not been many reports of retaliation against participants in the May Day marches.

Their self-understanding as workers was clear in how the day's events were planned. They called the protests for May Day, celebrated as International Workers Day in most of the world. They urged from the beginning they would walk out for the day and boycott as well; professional immigrant advocates wanted to tone down the protests. However people who see themselves as workers understand that what the society values them for is their labor and so it is by withdrawing their labor that they assert their dignity.

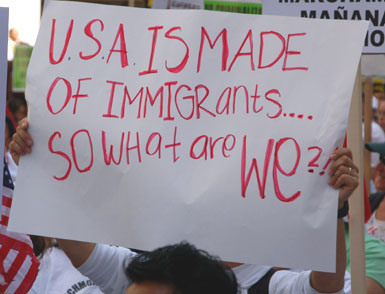

The hand painted signs at the rallies over and over again expressed outrage that Sensenbrenner, Tancredo, the Republican House of Representatives, or anyone would call them "criminals." They know, proudly, that their labor creates much of the country's wealth. "Si se puede; yes, we can!"

- Lofty goals: as David Bacon and Nativo Lopez point out in an important article on the marches, "people are ready and willing to fight for the whole enchilada." Winning it all, amnesty for all the undocumented, may be more than can be achieved in the short term. Can the movement find strategies and tactics to carry through an ongoing political process marked by repeated fights?

- Divisions by country of origin: in some places, immigrants from different countries worked together well on May Day; Chicago seems to have been a successful example of cooperation. But in others, especially where there are huge Spanish speaking, mostly Mexican-origin, populations, Latino nationalism could overwhelm immigrant unity.

- Divisions by immigration status: many of the "reform" schemes now in Congress would create a multiplicity of legal statuses based on time in the country, ability to document work, ability to pay fines, etc. If some version of these passes, will the group on the legalization track abandon the remaining, and still arriving, undocumented population? Experience says no, because in real life the new arrivals will have family ties to the "legals," but divisive pressures will grow.

- Leaders: anyone who saw these marches has to believe that the leadership exists in the immigrant communities to accomplish huge tasks. They've done it. But that functioning leadership is not, mostly, in the professional immigrant advocacy organizations, especially those in DC and especially those in the Democratic Party. Before the immigrants took to the streets, most of those in "respectable leadership" were open to various "reform" compromises coming out of Congress that would create a "guest worker" status that amounts to slave labor and "legalization" for only a minority of the undocumented. The leaders from the streets need to get into the mix with the professionals, if not completely displace them.

- Pulling up the ladder behind them: When does an immigrant stop being an immigrant? Historically, people have come to the United States, suffered as part of an exploited underclass of workers, gradually gained economic stability, won education and assimilation for their children, and then looked down on the next set of immigrants. Or, more succinctly, the objective for most immigrants has been to leave an immigrant identity behind and become "regular Americans." Can a civil rights movement be based in a population whose individual members are always striving to escape the group? Globalization and the disparities in wealth between north and south suggest that the incoming flow is not likely to decrease regardless of what kind of wall the U.S. builds on its borders. But can a movement be sustained with a changing cast of core participants? I guess we'll see.

No comments:

Post a Comment